We’re on our penultimate episode for our reading of Jack Bickham’s Scene & Structure. So, what does the bullet point Meister have to squeeze into an end of a book that 90% of its readers will probably never get to?

Well, first we give ourselves a little pep talk and then we see if we can make sense of all of these specialized scene situations. And, dear listener, there are a lot of them: interrupted scenes and sequels, non-viewpoint character scenes, flashback scenes, scenes with all-dialog, or all-action or unseen opponents or multiple agendas.

After all that high level specialization, we stepped back and take stock of the eminently practical lessons that we’ve learned from reading Bickham. Also in this episode we interview authors Val Neil, Lee Clark, and Nick Chiarkas about how they keep their readers engaged in their novels.

Want to hear more of our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast, SnarkNotes, and detailed write up of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

This Episode's Interviews

Continuing our discussion about Bickham’s plot templates for page turning novels, we asked some published writers if they’ve used any of these templates to turn up the suspense in their plots. Or is structure ultimately overrated?

Nick Charles

Nick Chiarkas writes historical crime thrillers set in mid-twentieth century New York City. The latest, Nunzio’s Way, was published this fall. For his books he draws on his many years in law enforcement as a police officer and lawyer.

Lee Clark

Lee Clark is the author of the Matthew Paine Mystery series featuring a South Carolina doctor who’s drawn into solving murders. Book four, Christmas Punch, was published this fall. You can buy her books here.

Val Neil

Val Neils writes dark urban fantasy set in the 1950s. The second book her Fall of Magic series comes out in December. You can buy her latest book, Dark Mind, here.

Specialized Structural Techniques (say that five times fast)

In chapter one of Scene & Structure, Bickham claimed that mastering structure would set the writer’s creativity free, unburdened by technical issues. Ten chapter later, however, we’re not seeing the “freedom” in his method. Who writes with structural units in mind, anyway? Asking for a friend…

In chapter twelve, Bickham rolls out eleven ways you can bend structure for special effects in the most abstract terms possible. We’re pretty sure we’ve reached reference manual territory, which we suspect is when readers breeze through (or check out of the book completely) the complicated concepts writers stuff at the end of the book, assuming no one will keep reading. Oh, but we keep reading, dear listener. Good thing, too! Where would you be without us?

Bickham's 11 Specialized Structures & Techniques

- Scene Interruption

- Scene in Scene

- Scene in Sequel

- Scene to Delay a sequel

- Scenes Started by a Non-Viewpoint Character

- Flashback Scenes

- Scene Fragmentation

- All-Dialogue Scenes

- All-Action Scenes

- Maneuver Scenes Against an Unseen Opponent

- Multiple Agenda Scenes

Scene Interruption

Sometimes you need a scene interruption just like sometimes you need an Interrupting Cow. They’re there for writers and Dad’s alike. We know it works for jokes and cows, but how what does it do in a novel? This technique delays the protagonist’s quest. It’s kind of in scene temporary setback in “mini-disaster” form.

Why would you do this? To delay the inevitable disaster. Or sometimes a minor or new character is just begging for their own scene (like Kramer from Seinfeld).

If you use this technique, Bickham says to set that min-disaster off quick and get right back to the main scene and its inevitable disaster at hand. Dallying to return to the main scene conflict annoys and confuses the reader.

Also, you can’t just go interrupting your scenes and sequels all willy-nilly. Bickham warns the writer this technique should only be used if you know the reader is hooked onto your scene. You’re delaying the inevitable disaster with another scene, and if the reader thinks you’re just playing with them like an Orca plays with its food, then you may risk more than just a cursory eye roll.

Scene in a Sequel

We call this the Bad Cop/Good Cop Strategy. Set up a conversation between two characters that either helps the protagonist work through his thoughts and feelings. Or create a sort of hostile character that criticizes and pisses of the protagonist. Both are options motivate your protagonist into action.

Scenes Started by a Non-Viewpoint Character

So if your story is the protagonist’s story and you’re supposed to stick to one viewpoint character at a time, how can a non-viewpoint character have control of a scene?

Bickham says you can simply make the viewpoint character answer a door unsuspectingly. The non-viewpoint character asks them a question or gives them new information, but the scene goal is in their hands.

Then Bickham offers some pretty solid advice here–not just for this strategy, but for writing in general.

Flashback Scenes

Ah, time travel. We all know this trick. The events in the story trigger a memory in your protagonist. They think back, recollect, and give the reader a new perspective of current events. But when do they occur? Bickham argues Flashbacks are a “scene” within a sequel, which is a scene that takes the place of the emotion and thinking component of a sequel.

As we sat waiting, Curt Lemon began to tense up. He kept fidgeting, playing with this dog tags. Finally somebody asked what the problem was, and Lemon looked down at his hands and said that back in high school he’d had a couple of bad experiences with dentists. Real sadism, he said. Torture chamber stuff. He didn’t mind blood or pain–he actually enjoyed combat–but there was something about a dentist that just gave him the creeps. He glanced over at the field tent and said, “No way. Count me out. Nobody messes with these teeth.”

But a few minutes later, when the dentist called his name, Lemon stood up and walked into the tent.

At this point, you may be wondering: these techniques seem pretty easy to understand.

All Dialogue Scenes

It says it’s all dialogue, but there’s more going on than you think. You need to have tags and the character needs to notice things in the moment. Observations and internalizations and descriptions. The dialogue is the cause and effect, everything else is support.

Bickham says “all dialogue” is an illusion of sorts. The reader only “reads” the dialogue, but throughout are descriptions of people, how they’re situated, how they speak, etc. When you write an all dialogue scene, it’s all about the stage directions and dialogue tags, like “he saw” and “she heard.” You need to orient the reader in time and place (also called signposting), since they may lose track of who is speaking.

Note the example below from Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice. I put non-dialogue elements in bold.

“My fingers,” said Elizabeth, “do not move over this instrument in the masterly manner which I see so many women’s do. They have not the same force or rapidity, and do not produce the same expression. But then I have always supposed it to be my own fault—because I will not take the trouble of practising. It is not that I do not believe my fingers as capable as any other woman’s of superior execution.”

Darcy smiled and said, “You are perfectly right. You have employed your time much better. No one admitted to the privilege of hearing you can think anything wanting. We neither of us perform to strangers.”

Here they were interrupted by Lady Catherine, who called out to know what they were talking of. Elizabeth immediately began playing again. Lady Catherine approached, and, after listening for a few minutes, said to Darcy: “Miss Bennet would not play at all amiss if she practised more, and could have the advantage of a London master. She has a very good notion of fingering, though her taste is not equal to Anne’s. Anne would have been a delightful performer, had her health allowed her to learn.”

Elizabeth looked at Darcy to see how cordially he assented to his cousin’s praise; but neither at that moment nor at any other could she discern any symptom of love; and from the whole of his behaviour to Miss de Bourgh she derived this comfort for Miss Bingley, that he might have been just as likely to marry her, had she been his relation.

Multiple Agenda Scene

Continuing the Conversation: The First Page Turners

Bickham’s all about the turners in Scene & Structure. So we got to thinking: where did these page turning genres come from? Who invented that wheel Bickham polished to perfection? Below we include the pioneers of the page turning craft. Enjoy!

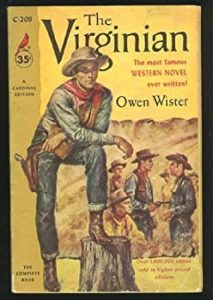

The First Western Novel

Published in 1902, The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains was written by Owen Wister, who was fascinated by the charm and adventure of the Old West.

Set in 1880’s Wyoming, the story chronicles the life and times of a cattle rancher (only ever referred to as “The Virginian”). The story is complete with all of the familiar western tropes: a schoolmarm love interest, a no good dirty rotten scoundrel, and a high and mighty protagonist who won’t stoop to the antagonist’s level.

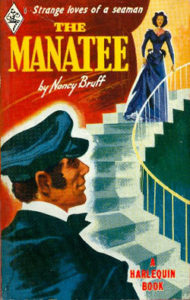

The First Harlequin Romance Novel

You won’t find plot analysis or even a Wikipedia article about Ms. Bruff nor an entry for The Manatee, considered to be the first Harlequin Romance. I’ve included the Jacket copy below.

MUTINY…MURDER…DESIRE…were Captain Jabez Folger’s pleasures. He loved nothing on land or sea but his ship, The Manatee, and the voluptuous sea-goddess who rode her bow. But Jabez Folger had a wife – wedded and bedded in one of the rare fits of humanity that made him seem like other men.

The Manatee is the bold, nakedly revealing story of his savage mismating…of the strange children he sired…of the unspeakable act that sealed his fate – and of the one secret he guarded, the secret of his devotion to depravity.

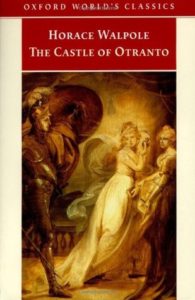

The First Horror Novel

The first horror novel isn’t Dracula, believe it or not. The first was The Castle of Otranto: A Gothic Story, published anonymously in 1764, and spurred a very popular genre in its time. The author, Horace Walpole, was suspected to be aesexual and revived the Gothic style not only in writing, but also in archetecture.

The book is a haunted house story, complete with ghosts and medieval themes. Forty years later, Jane Austen wrote a satire, Northanger Abbey, of the highly popular gothic novel. The protagonist was a huge fan of the Gothic Novel.

The First Fantasy Novel

The Worm Ouroboros seems to be the first true Fantasy Novel. The story is set in a midievel land and includes a classic hero’s journey protagonist on a quest. There’s the usual races of a fantasy world: demons, witches, pixies, imps, dwarves, and goblins, each with their own geographical stake called, aptly: Witchland, Impland, Demonland, etc.

E.R. Eddison, like Tolkein (they even knew each other!) incorporated Norse mythology, poetry, and maps into the narrative.

The First Science Fiction Novel

Of course, no list on the internet involving science fiction would be complete without Mary Shelley‘s 1818 Frankenstein. No, Jules Verne nor H.G. Wells hold the title of the first science fiction novelist.

We all know the story (probably from a movie adaptation that doesn’t resemble the original plot). If you ever get a chance to read it, however, it truly is a marvel. Macabre to its core, Frankenstein really does bring a dead body (parts) back to life. What follows is the scientific ethical question: if we can, should we? What happens when you play god?

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...