Chapter 1 - The Art of Fiction

We’re starting our first book – John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction. Let’s find out why writing instructors and bloggers keep recommending it to aspiring writers. We’ll try to figure out what Gardner means by aesthetic law and if the literary cannon is worth a read, and we’ll address the (male) elephant in the room, er book.

As promised, we’re also doing one of the assignments from Gardner’s book. We soft balled it this time, choosing to analyze the common elements of the superhero genre. On the podcast we discuss superhero costumes. If you want to hear more, check out our Patreon site where we discuss the “good guys fight each other trope.” Patreon is a way for us to cover our hosting services and production costs. In addition to giving out extra content, we hope to build a writers’ community. Check us out!

The Writing Exercise

List the customary elements of one or more of the following: a gothic romance, a murder mystery, a yarn, a TV situational comedy, or some other popular genre (Superhero Movies!). What are the philosophical implications of each of these elements? What do these elements seem to mean psychologically? What are some possible symbolic meanings? The genre’s listed are all “popular”; that is, their appeal is usually just adventure or entertainment. Suggest ways in which they might be elevated to serious fiction?

Aesthetic Law

Vocab (you know, just in case there's a quiz)

Aesthetic: a set of principles underlying and guiding the work of a particular artist or artistic movement.

“Every true work of art–and thus every attempt at art…must be judged primarily, though not exclusively, by its own laws.”

-John Gardner

Kim’s take on Gardner’s Aesthetic Law: It’s not that there’s a rule you can’t break (in fiction) but there’s guidelines…the reason it’s there is because when you break it you run into other problems.

Renee’s take: There are no such things as a set of hard rules when followed will produce a perfect story.

Continuing the Discussion: The (Western) Literary Canon

“In order to acheive mastery, he [the student writer] must read widely…Though the literary dabble may write a fine story now and then, the true writer is one for whom technique has become, as it is for the pianist, second nature. Ordinarily, this means university education, with courses in the writing of fiction, and poetry as well.”

-John Gardner

So what is the Western Literary Canon – the Canon Gardner refers to in his book? What does that term mean? Originally, the “canon” referred to the books of the bible sanctioned by the Church. Now, however, it’s a collection of curated texts, what many call “The Classics,” sanctioned by those who have the power to decide what represents “us,” our culture, traditions, and values (aka, what students read in school). Essentially, The (Western) Canon is a set of literature, art, and music, agreed upon by scholars and tradition, deemed “classics.”

Think of the canon as a kind of literary mix tape bestowed upon the masses. The problem: the “canon” has traditionally been made up of white men, because white men have traditionally been the ones in power. (Even today, women, people of color, the LGBTQ community, or and other marginalized groups are commonly excluded, denied, or flat out erased. Here’s looking at you NY Times Books). Prior to the 19th Century, Europe/England had curated that tradition. Given America was a colony of England, the colonists brought that canon with them. As America produced its own literary works, England and Europe discounted many notable American authors, claiming they didn’t really have a tradition; therefore, they would be excluded from the literary canon–deemed unworthy, essentially.

But then there was Edgar Allen Poe. Many poets we consider household literary names now were once discounted because they were American. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson weren’t yet considered “worthy” enough for European scholars because, well, Americans weren’t considered to have a culture. But then Edgar Allen Poe wielded the techniques of the European masters so well he could not be ignored. American authors were breaking the literary mold (see Walt Whitman’s free verse style) and gaining popularity with audiences in Europe, with or without the blessing of European scholars. Eventually, American literature was given a place at the “tradition” table.

So we ask you, Dear Listener. What texts in the 21st Century will be considered “classics” 100 years from now? Who will be in power and who will decide?

Further Reading

- De-Canon

- The Voice in the Margin UC Press

- Goodread’s Literary Canon Books

- In Defense of the Literary Canon by Aatif Rashid, Kenyon Review

"...always be aware of the possibility of

total defeat

whether the reason for that defeat

seems right or wrong"

What Craft Books might Gardner have read?

In the podcast we speculate on what sort of craft books were out when Gardner wrote The Art Fiction. A web search has come up with the following books.

- Elements of Style by Struck and White (1918 & 1959)

- Aspects of the Novel by EM Foster (1927)

- On Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande (1934, 1981, with forward by Gardner)

- The Lonely Voice: A study of the Short Story by Frank O’Connor (1962)

- On Writing Well by William Zinsser (1976)

- The Language of the Night by Ursula K. Leguin (1979)

- Creating Short Fiction by Damon Knight (1981)

- Writing Down the Bones by Natalie Goldberg (1986)

- How to Write A Damn Good Novel by James N. Frey (1987)

- The Writing Life by Annie Dillard (1989)

- Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury (1990)

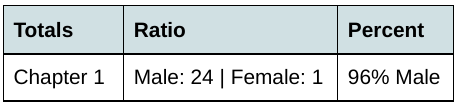

Gardner's Gender Ratio

A quick google search for Gardner’s The Art of Fiction will result in quite a few blogs and youtubers lamenting Gardner’s strict use of the male pronoun throughout this text. Your hosts, Kim and Renee, are old enough to remember when this was standard practice in written texts. But they also remember when it changed. Although we are quite aware of the “well, it was the eighties” argument, we also know conversations about gender equality and inclusion were already heated in Gardner’s time. He was an academic after all, teaching at San Francisco State and The University of Detroit.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, In The Art of Fiction, Gardner drops authors’ names like a toddler drops candy on Halloween. For each chapter, we will provide the number of mentioned authors but also the Gender Ration of said dropped authors. This goes beyond a pronoun. The exclusion warrants correcting. Or, as She-Hulk might say: Patriarchy Smash!

A Tribute to Gertrude Stein

Gertrude Stein was born in 1874. She is the author of Tender Buttons, The Making of Americans, and The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, among many other novels, poems, and plays. She was raised in Oakland, CA but spent the majority of her life in Paris where she hosted a salon featuring Pablo Picasso, Fitzgerald, and Henri Matisse, among others. She is the only female author referenced in chapter one of The Art of Fiction.

Let’s Not Get Sued (for Writing a Memoir)

Judith Barrington’s Writing the MemoirChapter 8, 9, & Appendix Subscribe to our Newsletter Writing (and publishing) a memoir can be nerve wracking. What if the people you’re writing about...