Enough with the theoretical, in this episode we get some practical advice out of Gardner’s book, The Art of Fiction. Specifically, he tells us what we’re doing wrong. We discuss a few of what Gardner calls clumsy errors before moving onto Faults of the Soul – Sentimentality, Frigidity, and Mannerisms.

The Writing Exercise

Write an acceptable example of purple prose–that is, highly self-conscious and arty prose made acceptable by subject, parodic intent, voice, etc

Gardner's Common Errors (and spelling ain't one of 'em)

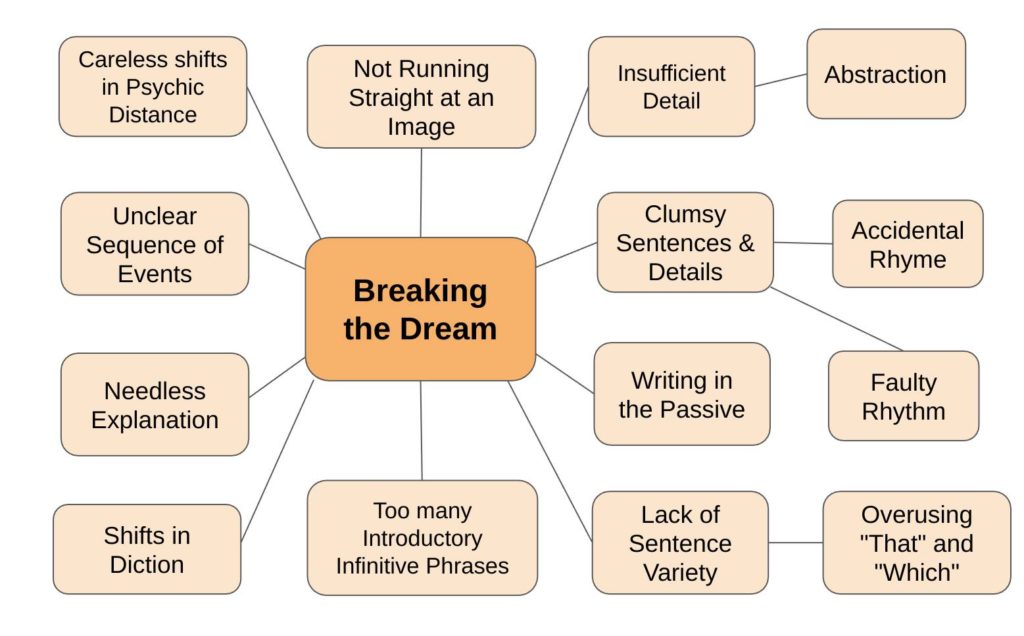

What Happens When We Error?

So what happens when we error? According to Gardner, “we are abruptly snapped out of the dream, forced to think of the writer or the writing.” How does this happen? Below are the writing mistakes that “break the dream.”

*For examples of these error and how to fix ’em, go to Patreon.

Errors we cover in the Episode w/ Examples (you're welcome)

Elevated Shifts in Diction (ie: trying to sound fancy)

Here’s an example of stylistic sin, from none other than the master himself:

The writing has most of the usual qualities of falsely elevated diction: abstract language…cliche personification, Latinate language where simple Anglo-Saxon would be preferable.

-John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction

We’re confident that one was pretty self explanatory.

Too Many (Introductory) Infinitive Verb Phrases

What the heck is an Infinitive Verb Phrase? Starting sentences with verbs ending in “ing” and sometimes “to.” Not to be confused with “ing” subjects (what’s called a gerund, ie: Running is fun).

Example of Introductory Infinitive Verb Phrase:

Running to the store, I picked up some apple juice.

Gardner says, used intentionally, the infinitive slows down the action. Used badly, it “chops up the action in fits and starts.”

It creates other problems too, like the sense something is happening almost by itself. The reader has to juggle multiple actions at once must also keep the action in mind before the subject.

So how should writers use infinitives?

Here’s an example from George R.R. Martin, a master at writing action clearly and sequentially (IRO: In Renee’s Opinion).

Note where Martin puts verb phrases in a sentence (in italics).

Ser Vardis swiveled, bringing up his heavy shield. Bronn turned to face him. Their swords rang together, once, twice, a testing. The sellsword backed off a step. The knight came after, holding his shield before him. He tried a slash, but Bronn jerked back, just out of reach, and the silver blade cut only air. Bronn circled to his right. Ser Vardis turned to follow, keeping his shield between them. The knight pressed forward, placing each foot carefully on the uneven ground. The sellsword gave way, a faint smile playing over his lips. Ser Vardis attacked, slashing, but Bronn leapt away from him, hopping lightly over a low moss-covered stone. Now the sellsword circled left, away from the shield, toward the knight’s unprotected side. Ser Vardis tried a hack at his legs, but he did not have he reach. Bronn danced farther to his left. Ser Vardis turned in place.

– from George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones

Martin places the verb phrases after the subjects, so the reader doesn’t have to wait for who is doing what. This is particularly important when writing movement. Who is doing what should be in the right order, one thing at a time, so the reader can see it. EVEN if things are happening at once (infinitives allow Ser Vardis to both swivel AND bring up a shield in one fluid movement), even though the reader can only read one word at a time.

Imagine if Martin wrote: “Bringing up his heavy shield, Ser Vardis swiveled.” Or: Swiveling, Ser Vardis brought up his shield.” Yuck… Logic isn’t the only thing swiveling in these sentences.

Also, note the sequence of events, how organized every movement is in the paragraph. Martin practically gave stage directions.

Faults of the (lol) SOUL: Sentimentality, Frigidity, Mannered Writing

Just in case you were a little self conscious about your grammatical errors, did you know they can also cause cancer? These errors (of the soul) include: Sentimentality, Frigidity, and Mannerisms.

Sentimentality: Writing with unearned emotion, drama, or moral.

Kim and Renee decided that if it keeps hitting your heartstrings (admit it, you still cry when Frodo goes to the Undying Lands), then it earned your tears. If it only works once–or hardly the first time–and it seems ridiculous, then it’s probably sentimental and you should throw stones at that writer.

I’m pretty sure Mr. Wilde had this scene in mind…🙄

Frigidity: Cheating the Reader

Definition: When a writer shows a flippant disregard for the reader’s investment in the story, which is the fault of the writer not connecting emotionally with the character. Action heroes come to mind.

Renee deeply apologizes for the following example. If you’re a millennial, then you were most likely spared the Rambo movies. Whoever you are, Renee in no way suggests you watch it. Don’t go on. Go back while you still can. This is not the way. Take heed and go no further…

Dude, I warned you…

Mannered Writing: Writing that sacrifices readability.

The writing is so elaborate or verbose the reader either can’t connect with the characters or follow the plot (as per our Purple Prose activity and discussion in the episode).

Example of Mannered Writing (discussed in the episode):

But then again I wonder if what we feel in our hearts today isn’t like these raindrops still falling on us from the soaked leaves above, even though the sky itself long stopped raining. I’m wondering if without our memories, there’s nothing for it but for our love to fade and die.”

– from The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

Now compare that with the (non-mannered) prose style from another book from the same author, with a character talking about a similar topic: memories.

Example of straightforward prose (same author, same subject):

Memories, even your most precious ones, fade surprisingly quickly. But I don’t go along with that. The memories I value most, I don’t ever see them fading.

– from Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

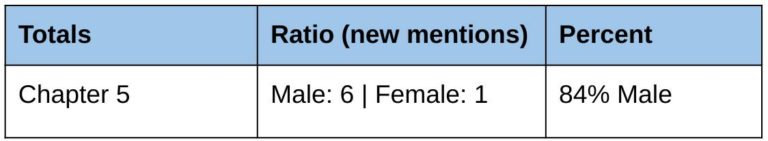

Gardner's Gender Ratio for Chapter 5

Continuing the Conversation: Sentimentality

Thomas Kincade, Painter of 🤮🤮🤮

So what do literary types mean by the term, Sentimentality? It refers to a style of writing popular in the 18th Century. Think over the top emotion, which eventually just makes us desensitized.

Abolitionist Poetry was a defining genre during that time, such as “A Slave’s Address to British Ladies“, written by a white woman appealing to an audience of mothers.

Hear, and help the kneeling Slave.

Think, how nought but death can sever

Your lov’d children from your hold ;

Still alive—but lost for ever—

Ours are parted, bought and sold!-Susanna Watts

The Sentiment goes: how would you feel if your child was ripped from your arms, bought and sold into slavery and never seen again? That’s why slavery is wrong and we should abolish the practice! Now who is with me!?

If this poem pings your cringe-dar, you’re not alone. There’s obvious reasons a contemporary reader takes issue with this. One, this experience is horrific, but feels empty and preachy at the same time. Two, a few lines hardly does the tragedy justice. Three, being a mother does not an authority on loss make. In other words, this educated white lady is assuming, somehow, she can invoke the sympathies of a black slave whose child was sold into slavery–and that it’s an effective strategy. The sentiment, therefore, does not ring true. It’s false, rather presumptuous, and leaves a bad taste in our mouth.

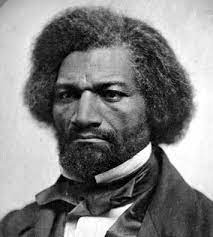

Now, take for example the following, which is much more effective commentary on abolishing slavery.

Interested in this topic? Here are some links:

- Pamela; or Virtue Rewarded by Samuel Richardson

- An Apology for the Life of Mrs. Shamela Andrews by Henry Fielding

- The Critic; or A Tragedy Rehearsed by Richard Sheridan

- Sentimental Poetry

A Tribute to Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf (Adeline Virginia Woolf) was born in 1882 and died in 1941. One of the most important and influential authors of the 20th Century, she was an essayist, memoirist and novelist in England. She was educated at King’s College in London and was a defining figure of Modernism in literature. She, along with her husband, co-founded Hogarth Press. Her first book, The Voyage Out, was published in 1915, followed by some of her most famous works: Mrs. Dalloway (1925), Orlando (1927), To the Lighthouse (1928), and A Room of One’s Own (1929). Her work tackled subjects such as class and suffrage, and played with form and langauge. She pioneered “stream of consciousness” writing, breaking away from the style of the Victorian novel.

I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.

-Virginia Woolf

What’s Really Happening When AI Writes? An Interview with Bill Moore

We've been putting AI chatbots through creative writing challenges, but what are these systems actually doing when they write? In this episode, we bring in AI expert Bill Moore. Bill...