Chapter 6 - The Art of Fiction

Gardner promises to show us the proper way for the young writer to achieve artistic mastery. Doesn’t that sound marvelous? We take him to task on his analysis and advice on the techniques of Imitation, Vocabulary, The Sentence, Point of View, Delay and Style from chapter 6 of The Art of Fiction.

And for this week’s activity, we practice the art of Delay (the paragraph before the climax of a character discovering a body). On the episode, we workshop Kim’s paragraph and decide what makes for a truly tense elements goes into building tension and developing “the joy of having something unfold in front of the reader.” Curious for more words of wisdom? Listen to our extended discussion during which we discuss Renee’s paragraph about a runner discovering a body.

The Writing Exercise

Write the paragraph that would appear in a piece of fiction just before the discovery of a body. You might perhaps describe the character’s approach to the body he will find, or the location, or both. The purpose of the exercise is to develop the technique of at once attracting the reader toward the paragraph to follow, making him want to skip ahead, and holding him on this paragraph by virtue of its interest. Without the ability to write such foreplay paragraphs, one can never achieve real suspense.

Leveling Up w/ Gardner's Techniques

- Writing Exercises are good for you (like Broccoli and Vitamins)

- Imitate old stories and Copy old prose

- Keep the Vocab simple and consider learning Greek or Latin

- Experiment with looooong sentences

- Learn how to identify the beats in language

- Point Of View (Essayist 3rd Omniscient Gardner’s ❤️)

- Delay the Climactic Scene

- Develop your Voice (but don’t act like you’re trying to develop your voice…I don’t know, write casual)

Gardner's POV on Point of View

First Person POV

Here’s an example of First Person

Sadness crept over me—a sadness I didn’t question, a sadness so profound I understood it could not have come from life, or any source within my conceptual scope, but instead seeped into me from the very air, from the whole extant universe in which I was less than a speck, sadness that was not emotion but the awareness of vast emptinesses.

— Frank Conroy from Stop-Time: A Memoir

Gardner’s not a huge fan of first person POV, nor the writer who wields it, apparently.

First-Person allows the writer to write as he talks, and this may be an advantage…but first person does not force the writer to recognize that written speech has to make up for the loss of facial expression, gesture, and the like, and the usual result is not good writing but only writing less noticeably bad.

Third Person Subjective

Gardner isn’t a fan of this POV either. He also gives it short shrift, saying “that something is wrong when it becomes the dominant point of view in fiction.”

Here’s an example. Note how close the psychic distance is. It’s the thoughts in real time in Lilly’s mind in her voice. But it’s third person (in this story, the POV actually shifts between two characters…so in a way, it’s mixing third person subjective with omniscient. Clever.

But no, there’s no time for that. There’s time for going out with the boys, and stayingout till all hours, and never mind that some of the boys are women, no, never mind that, it’s just, I’m sorry, honey, I’ll be home late tonight, don’t wait up, and don’t worry, honey, we’ll get around to a little evening out for ourselves one of these days, too.

Well, baloney. He wasn’t fooling anyone. And she was going to prove it.

C.J. Hribal, from “Morton and Lilly, Dredge and Fill”

Third Person Objective

Gardner claiims this POV is good for short fiction and that “its limits are obvious…” …um…yeah…wait, what?

Gardner describes the third person objective as “identical to third person subjective except that the narrator not only never comments himself but also refrains from entering any character’s mind.” Think the unthinking camera, as objective as possible.

He picked up the two heavy bags and carried them around the station to the other tracks. He looked up the tracks but could not see the train. Coming back, he walked through the barroom, where people waiting for the train were drinking. He drank an Anis at the bar and looked at the people. They were all waiting reasonably for the train. He went out through the bead curtain. She was sitting at the table and smiled at him.

Ernest Hemmingway, “Hills Like White Elephants“

Authorial-Omniscient POV

In other words, the narrator is as all knowing (and sometimes as opinionated) as a god. The narrator sees what all of the characters see, what they feel, what they think. All perception is available and “occasionally dips into the third person subjective to give the reader an immediate sense of why the character feels as he does, but reserves to himself the right to judge” (Gardner).

The narrator not only knows all, but can be a little judgy too (as gods are or tend to be).

There was a great deal of fussing to be done before Mr. Summers declared the lottery open. There were the lists to make up—of heads of families, heads of households in each family, members of each household in each family. There was the proper swearing-in of Mr. Summers by the postmaster, as the official of the lottery; at one time, some people remembered, there had been a recital of some sort, performed by the official of the lottery, a perfunctory, tuneless chant that had been rattled off duly each year; some people believed that the official of the lottery used to stand just so when he said or sang it, others believed that he was supposed to walk among the people, but years and years ago this part of the ritual had been allowed to lapse. There had been, also, a ritual salute, which the official of the lottery had had to use in addressing each person who came up to draw from the box, but this also had changed with time, until now it was felt necessary only for the official to speak to each person approaching. Mr. Summers was very good at all this; in his clean white shirt and blue jeans, with one hand resting carelessly on the black box, he seemed very proper and important as he talked interminably to Mr. Graves and the Martins.

Shirley Jackson, from “The Lottery”

Essayist-Omniscient

Not to be confused with authorial omniscient, the god-like narrator in essayist omniscient POV telling the story has a personality, a dialect, a tone, and an opinion. I’m pretty sure Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) would hit the mark.

Gardner mentions Charles Johnson in reference to the Essayist-Omniscient. It’s also the first and only black writer Gardner refers to in The Art of Fiction, a rare feat, to be sure.

From the table, they could see through the kitchen window that Jackson and his two assistants had straightened out Lavidia’s legs and were carrying her on a stretcher to the open door of a hearse idling just yards from the front porch. Brown’s eyes rolled toward the ceiling; he said something pious in a deep voice, reached across the table, and stroked Faith’s hand. “What will you do now, child?”

Do? Faith paused, squinting her eyes to clear her head. The kitchen had changed. You could locate nothing misplaced, nothing out of the ordinary, for as a housekeeper Lavidia was meticulous; but the kitchen’s former gloss of permanence was gone. Its smell was still that of the dry cotton fields just outside the open window above the sink, of browning bread Lavidia had baked just two nights before; yet Lavidia was gone. Though old, dissipated, sometimes evil, she had been the focus of the farmhouse since her husband’s death, its most crucial node, surely its mistress. Without her the kitchen, the house, the world beyond fell apart. Fruit cabinets on the wall still held sweet jellies preserved in the odd-shaped bottles Lavidia salvaged like a scavenger from house and yard and rummage sales; her stiff mops and silver pail still rested in the corner by brooms she’d assembled by hand. Then what had changed? Certainly not the things themselves. Studying Lavidia’s dresses heaped in a washtub by the door, her pipes in their dusty rack on the kitchen table, and dry lifeless wigs, Faith felt her answer emerge from the contours of these objects: none of them was for her; they belonged, related to no one. Even Lavidia, perhaps, had not made them her own, because — with her death — they seemed suddenly freed to be as they were. Empty things, cold, without quality, distant. Without order — it was evident — there could be no life, no sense to things, no way to awake in the stillness of morning and move from the day to and through the terror of eveningtime.

-Charles Johnson, from Faith and the Good Thing

Continuing the Conversation: Mimesis

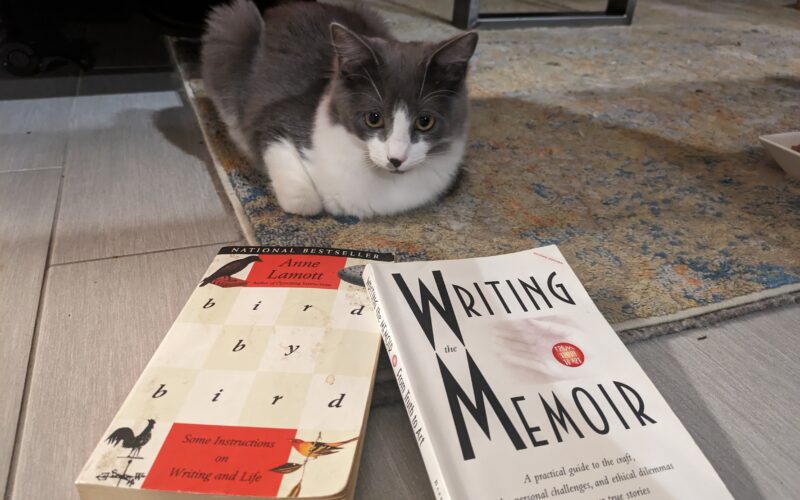

So are writers born or made? Depends on who you ask. There is no shortage of writing craft books on the market (given Renee has like 50+ of them and without them we would not have this podcast). Aristotle’s Poetics and Plato’s Republic were perhaps the oldest, at least to survive the ancient world, and define the tenants of western storytelling to this day. Focusing on tragedy, Aristotle organized a story into the structure we know so well: a beginning, middle, and end. He said story and poetry (also the sculpture and the flute) were all a mimetic, as in, copies of the world around us.

Aristotle said story and poetry (also the sculpture and the flute) were all a mimetic, as in, copies of the world around us.

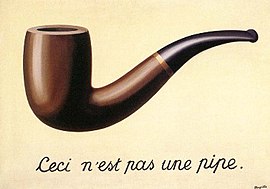

A story is not reality but a simulation of life, just like this painting “is not a pipe” It’s a painting of a pipe. Get it?

Plato also saw poetry, writing, and art as a kind of copy; however, he was most concerned with the purity or closeness to the real. Since poets like to play with imagery, meaning, and such with their metaphors and similes, Plato called poets liars.

The philosophy that story is imitation laid the foundation for most of our most famed writers’ educations. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Byron, Milton all received classical educations. But as all beginning creative writers discover: learning what makes a good story is only one piece of the equation; how one learns to imitate is quite another.

The Art of Learning Creative Writing

So how did these greats learn to “copy” the world so artfully, expertly, impressively? Is it even possible to learn to be a creative writer? Or, indeed, creative? It depends on who you ask. Gardner advocates for writers to have a background in a university education, with an emphasis on the canon and the classics. Today, all creative writing departments on college campuses have agreed the workshop model, a group of writers getting together discussing and critiquing a draft, is the best method to learn to write creatively. Yet, most MFA programs require courses that include analysis of published work, both contemporary and classic.

So what if you don’t have access this (very expensive) model? Can one really teach themselves?

But what, exactly, does a creative writer teach oneself to write? Today, we have craft books, but how did creative writers develop craft before there was a writing craft book market? Gardner mentions and even advocates copying, or copywork as I’ve seen it named on the internet, as one technique. Essentially, you pick a piece of writing you admire and you copy it word for word, preferably by hand (handwriting as opposed to dictating on the computer creates a deeper learning experience).

Hemingway claimed to have taught himself, but he did receive instruction from Ezra Pound. Bukowski went to community college, but never went to university. One could argue Jane Austen (and most female authors of her time) taught herself. She received some formal education until the age of ten, but that was pretty standard for upper middle class women in the 19th C. The rest of her education took place at home. (Luckily, her father had an extensive library).

Here are a list of some famous writers who used this method: Benjamin Franklin, Jack London, and Ernest Hemingway.

Additional Resources & Further Reading

- Aristotle’s Poetics

- Plato’s Republic

- Mimesis Wikipedia

- “In Defense Of Creative Writing Classes and Nuts & Bolts” by Richard Hugo.

- “Creative Writing in English Education: An Historical Perspective” by Alice Glarden Brand

- “Towards a Creativity Framework” by Irina Surkova

- “The Rise of Creative Writing” by DJ Myers

- “Want to Become a Better Writer? Copy the Work of Others!” by Brett & Kate McKenzie

A Tribute to Joyce Carol Oates

Joyce Carol Oates (still alive today!) was born June 6th, 1938. Winner of the National Book Award and National Humanities Medal (among many, many others) she has created an impressive body of work–a staple of contemporary American fiction. She was the first in her family to graduate high school and received her Master’s Degree from University of Wisconsin-Madison. Extremely prolific, she is a novelist (58 novels!), playwright, poet, and short story writer. Her most famous story, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been,” is heavily anthologized.

Workshop: Naming Names in your Memoir

For this week’s workshop episode, Renee wrote about the brief time she spent as a child in Pacific Grove, CA, taking care to identify specific streets and locations as...