Think ChatGPT can finish your creative writing exercises? Let’s find out! In this episode we’re testing the cutting-edge artificial intelligence on some old school writing prompts. We dug out our copies of John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction and typed in two of the back-of-the-book exercises. Faster than you could say “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” out came … words. Listen to us workshop those words: the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Then, having proved we’re still at bit away from having an AI write our novels, we returned to Scene & Structure and our own literary self-improvement. In the final chapters of the Jack Bickham’s book, we learn the secrets to ending chapters and take a dive deep into how a full novel is structured (especially that “boggy middle”).

Want to hear more of our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast, SnarkNotes, and detailed write ups of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

Dear ChatGPT, F*** You. Sincerely Yours, Writers.

First they came for the scriveners, but I did not speak out because I was not a scrivener. Then they came for the type setters but I did not speak out because I was not a printer. Then they came for the books, but I did not speak out because I did not own a bookstore. Then they came for the writers, and there was no one left to speak out for me…

If you’re a writer or artist, no doubt you’ve heard about the newfangled technology that’s come to take your creative jobs. If you’ve even glanced at the internet, Chat GPT (affectionally called “Chatty” by your fearless co-hosts) and DALL-E, an AI capable of winning art contests, have surely appeared on your radar. Many a budding author and artist are panicking over the implications (I wouldn’t major in technical writing or copywriting if I were you). But how worried should novelists and poets really be?

In this episode, the trained scientist, Kim, and the teacher with her fancy writing degree, Renee, put Chatty to the test with some of John Gardner’s writing prompts to see how well (or not so well) AI can describe landscapes from the point of view of a bird without mentioning said bird, or a lake as seen by someone who has just committed murder.

So, how doomed are we? Do we as authors need to retire our quills and bow down to Chatty, our AI author overlord? Or is AI only as eloquent as the programmers who programmed them and the quality of content on the internet from which they pull for inspiration? You’ll have to listen this week’s episode to find out.

The End of Bickham's Scene & Structure

We did it! We’ve reached the end of Bickham’s Scene & Structure. For better or worse, both Renee and Kim were generally pleased with the first five chapters (and appreciated the appendix), but suggest you skip through the “boggy middle” to final chapter fourteen, “The Scene Master Plot and How to Write One.” We dispense with the details below.

Chapter 13: The Structure of Chapters

What Questions do YOU ask Authors at Writing Conferences?

Bickham starts this chapter by answering the (apparently) most pressing, most asked question at writing conferences ever. It’s not ‘how to make money as a writer?” It’s not “What’s the difference between show, don’t tell anyway?” Neither is it: “Why was the registration fee more expensive than the hotel room?” Or “Where’s the bloody bar?”

Nope. It’s: “How long should a chapter be?” Now, whether or not you’ve ever asked yourself this question (Renee thinks it’s a silly question), Bickham does give an answer: 4 pages of 3 or 4 scenes.

Look at that! You didn’t even have to read the chapter to find out. You’re welcome.

Chapter Structures; or, Don't End the Chapter When your Character Goes to Sleep

Bickham advises writers to end chapters so that they “link forward” so your reader is compelled to keep reading. Remember, Bickham’s all about ‘hooking readers’ and his advice is akin to the Netflix cliffhanger episode ending model to encourage binge watching. Hmmm, binge reading has a nice ring to it…

Good places to end a chapter:

- The moment of disaster ending a scene

- Right in the middle of the conflict.

- At a point your protagonist thinks “there is no way out”

- The start of new action

- At the end of a sequel, when the protagonist has made a decision.

The Scene Master Plot and How to Write One

Dear Writer, Reader, and Listener,

Congratulations! You’ve made it to the end of Bickham’s Scene & Structure. For this chapter, Bickham saves the best for last (sort of: we also recommend chapter one, two, three, four and five) with his play by play breakdown of a Bickham-style novel. Before you begin, however, Bickham warns this is not a formula with which one can Mad-Lib a successful page-turning novel, but a guide or example which illustrates what Bickham considers a novel to be. With that said, he asks that you think about what you think a novel is and design your own model accordingly…

A Bickham Novel, Chapter by Chapter

What what does a “page turner” look like, chapter by chapter? Here’s a quick summary of Bickham’s novel outline (if you want details, you’ll have to read the SnarkNotes on Patreon).

- Chapter 1: Establish the Main Character’s Status Quo and the Major Change to it

- Chapter 2: Establish Villain’s Goal (which makes the reader worry)

- Chapter 3: Introduce Supporting Characters/Backgrounds

- Chapter 4: Establish Secondary Characters/Roles and introduce the start of a three chapter quest.

- Chapter 5: Protagonist helps another struggle through a disaster then hops back to his side quest.

- Chapter 6: Romantic Interest gets fleshed out.

- Chapter 7: Protagonist confronts Villain; an action sequence ensues.

- Chapter 8: Continue on with the disaster to end three chapter quest. Hero will narrowly escape.

- Chapter 9: Villain plots new plan and perhaps blames a henchman.

- Chapter 10: Protagonist reviews all that has transpired; the romantic subplot intensifies.

- Chapter 11: A fast paced chapter of scenes “butting up against each other.” Include ticking clock.

- Chapter 12: Villain reveals his motives; the Protagonist fails in some way.

- Chapter 13: Romantic Lead tries to help but just gets in the way

.

- Chapter 14: The Villain escapes; Protagonist starts “final novel game-plan.”

- Chapter 15: Damsel in Distress.

- Chapter 16: Time is running out for the Protagonist to solve the mystery; save the girlfriend.

- Chapter 17: Romantic lead thinks there’s no hope for the relationship.

- Chapter 18: Ultimate Showdown between Villain and Protagonist.

- Chapter 19: Hero faces a choice, which goes against moral code (which, of course, he refuses). Hero wins.

- Chapter 20: Tie up loose plot ends; Romantic Lead and Hero end on a dubious note.

As you can see, tucked at the end of Bickham’s book is the what and the when of character development, plot points, side plots, etc all stuffed into a Bickham-esque formulaic novel outline. What you won’t get, however, is how to do these techniques. You’ll just have to continue to tune into the podcast to hear how that’s done…

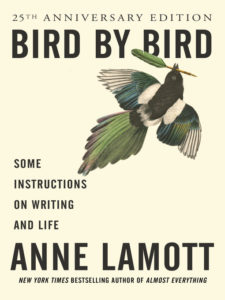

Our Next Book....Drumroll Please...................

Yep, we’re reading and analyzing Anne Lamott‘s insanely popular craft book, Bird by Bird. No doubt you have this iconic text on your bookshelf, fully read, annotated, with a completed manuscript ready for the publisher to show for it. But just in case you haven’t cracked the spine, we’ve got you covered. We’ll dive deep into what makes this book so popular, if it truly earns its reputation, and, like…what’s actually in this thing, anyway? Stay tuned, Dear Listener. Stay tuned.

Continuing the Conversation: Constrained Writing Technique

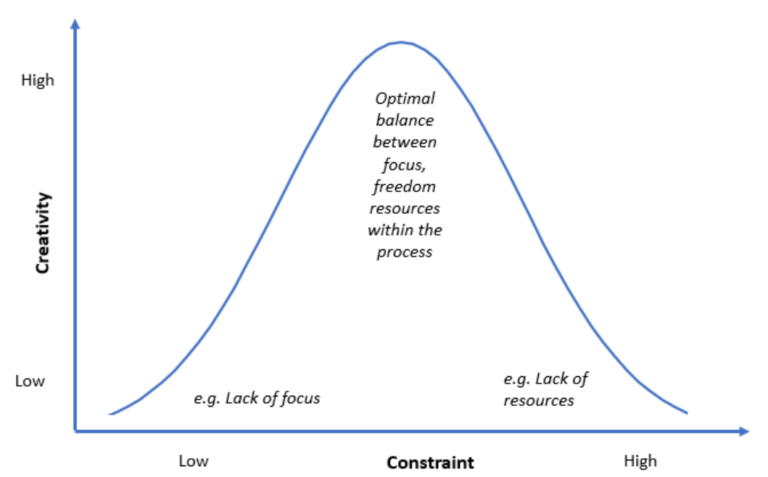

Has the wide chasm of creative possibility left you staring at the blank page for hours? Have you talked yourself out of one plot after another, or exhausted your store of ideas? Perhaps you should try Constrained Writing. This technique involves administering some kind of constraint to your creative task. Sonnets, Villanelles, Pantoums are type of constraint, so is a specific theme or form.

Researchers have found too much creative freedom can backfire. Like many creative techniques, this method is nothing new. It’s also very, very effective. Prompts, too, are a type of Constrained Writing. Below are some famous examples of the Constrained Writing Technique in action.

Thematic Plot Rules

What seems like just a science fiction speculative thought experiment in a story about robots in a near future society was actually a Constrained Writing device for all of Asimov’s subsequent short stories novels. The plots of all of these stories revolve around these three laws put into action.

Asimov's Three Laws of Robotics

- First Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- Second Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- Third Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Isaac Asimov coined the laws of robotics, a safeguard against the eventual rise and danger of developing robots and AI, in his 1942 short story, “Runaround,” and later other books, such as I, Robot.

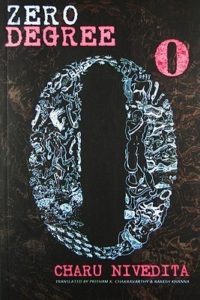

Numerical Constraints

Charu Nivedita‘s 1998 Zero Degree utilizes a numerical restraint: the author only mentions numbers equivalent to nine. Considered a form of Meta-Fiction, it is included in HarperCollins’ 50 Writers, 50 Books – The Best of Indian Fiction.

Word Choice & Sentence Constraints

Much like ChatGPT, Jonathan Ruffian culls the internet – specifically content about guns and violence – to create A Gun Is Not Polite: Violent Sho(r)t Stories & Bloody Pistol Poetry.

This book of poems and short stories contains a word for “gun” in every single sentence. What transpires is an effective commentary on violence and American society in poetic form.

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...