Chapter 7 - The Art of Fiction

Wow! We’ve gotten to the final chapter of John Gardner’s book, The Art of Fiction, and it’s all about plotting your short story, or novella, or novel (there are, apparently differences). We also learn some fancy plot vocabulary. Oh, and the stripper? Her name is Fanny, and her story is the example that Gardner uses to explain how to devise a plot. Our guess is that most readers don’t make it to Fanny, but trust us, she’s totally worth it.

The Writing Exercise

Take a simple event: A man gets off a bus, trips, looks around in embarrassment, and sees a woman smiling. Describe this event, using the same characters and elements of setting, in five completely different ways (changes of style, tone, sentence structure, voice, psychic distance, etc). Make sure the styles are radically different; otherwise, the exercise is wasted.

Gardner's One Weird Trick to Plotting "Good Art"

- Work backwards (from) or forwards (to) a central conflict.

- Give your character agency and trouble (trouble should be both internal end external).

- Beginning, exposition should be shown, not told.

- Middle: make them suffer, go to great lengths.

- Ending: Denouement: wrap it up but not too tightly.

- His one weird trick? Give that $#@% a theme, yo.

Pick a Plot, Any Plot

In this chapter, Gardner spends a lot of time describing what types of plot one could write, what’s wrong with those plots and…well, that’s it. If you want to know how to write any of these plots, you’ll have to read a different book. Below are a few he covers. Keep in mind his favorite plot, the one that–you guessed it–rules them all is the Energeic Plot.

Plots Gardner Complains About

- Argumentative Story

- Picaresque Plot

- Allegorical Plots

- Secret Logic Plots

- Mythological Plots

Vocab (c'mon, you know he gave vocab tests...)

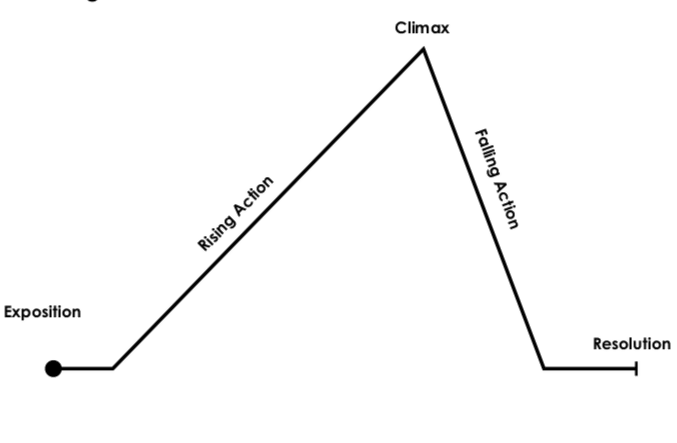

Energeia (or Energeic Plot): Aristotle (him again…why aren’t we surprised?) coins the term, Energea, in Physics. And, indeed, the term is used mostly in science to describe the laws of movement. However, in terms of writing, an Energeic Plot is a Goal Centered Plot.

And although you may not be able to parse the difference between actuality and potentiality, you, Dear Writer, are probably very familiar with the Energeic Plot.

May I present the one…the only…STORY ARC! (And the crowd goes wild!!!)

The Argumentative Plot

An argumentative story is one with an opinion, an agenda. Similar to an Allegorical Plot but less preachy.

For example, the underlying arguments in older science fiction, like The Time Machine, Brave New World, and Fahrenheit 451, can sometimes get in the way of its own plot.

Check out this nugget from Heinlein’s Stranger in a Strange Land.

“Please, Jubal. He’s got to learn how to behave. I’m trying so hard to train him.”

“Hmmph! You’re trying to force on him your own narrow-minded, middle class, Bible Belt morality. Don’t think I haven’t been watching.”

“I have not! I haven’t concerned myself with his morals; I’ve simply been teaching him necessary customs.”

“Customs, morals-is there a difference? Woman, do you realize what you are doing? Here, by the grace of God and an inside straight, we have a personality untouched by the psychotic taboos of our tribe-.–and you want to turn him into a carbon copy of every fourth-rate conformist in this frightened land! Why don’t you go whole hog? Get him a brief case and make him carry it wherever he goes-make him feel shame if he doesn’t have it.”

“I’m not doing anything of the sort! I’m just trying to keep him out of trouble. It’s for his own good.”

Jubal snorted. “That’s the excuse they gave the tomcat just before his operation.”

So you noticed how he addressed her as “woman” too…yeah…Gardner and Heinlein would have enjoyed chatting over drinks.

The Picaresque Plot

These novels revolve around a roguish protagonist from low born society and their episodic adventures. Think Don Quixote or Huckleberry Finn. In some ways, these novels are almost the equivalent of a trade paperback, but there’s no real character arc tying the adventures together. Although the protagonist may learn a lesson of some kind, those lessons rarely carry into the next chapter. Gardner claims these stories are only interesting if the protagonist is in actual peril or danger.

The Allegorical Plot

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. Orwell’s Animal Farm. Melville’s Moby Dick. Novels or stories with Allegorical Plots use symbols–such as animals on a farm to illustrate communist Russia, or a story about a boy and his whale–to carry a moral agenda or teach some lesson, usually religious or political. Gardner warns writers against it, saying the reader feel manipulated because the plot has been manipulated to fulfill an agenda.

Continuing the Conversation: Social Science Fiction as Protest Literature

Many genres of science fiction exist: Hard Sci-Fi, Space Opera, Apocalyptic, Dystopian, Time Travel, etc, etc, etc. One sub-genre, Social Science Fiction, tackles sociological and psychological themes. Allegorical and/or argumentative in its plot, the first science fiction novel was Social Science Fiction: Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. Little do people know, she also wrote the first Post-Apocalyptic novel, The Last Man.

Science Fiction writers have wielded the genre for its unique ability to remove us from the context of our moral failings or conflicts so that we can un-desensitize ourselves and see what we’ve chosen to forget (District 9 expertly pulls this off). With a rich history of Utopian science fiction, Soviet writers in the 20th Century wrote in the genre as a form of free expression (or propaganda). And although we’re all familiar with Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale, a long, rich history of science fiction female authors have used the genre to draw attention to gender equality, such as Octavia Butler’s male pregnancy short story, “Bloodchild,” or critique patriarchy, like in Joanna Russ‘ “When It Changed” which is similar to Charlotte Gilman’s novel, Herland, written in 1916.

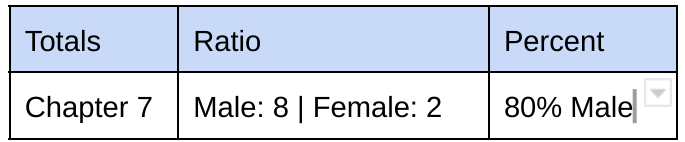

Gardner's Author Gender Ratio

Gardner only mentions ten new authors in Chapter 7, only two of which were women: Flannery O’Connor, Eudora Wetley.

A Tribute to Flannery O'Connor

Flannery O’Connor (1925 – 1964) was a short story writer, novelist, and columnist. Her stories, “A Good Man is Hard to Find,” is heavily anthologized and read by just about every undergraduate in the United States. She received her MFA from the Iowa Writer’s Workshop where she began drafting her first novel, Wise Blood. Although she wrote two novels, she is most famous for The Complete Short Stories, a collection curated posthumously and which was awarded the National Book Award in 1972. Gardner mentions O’Connor, along with Eudora Welty, for the unique, iconic Southern Gothic style in which they write.

The Secret to Getting Your Short Stories Publish

Okay, maybe that's a bit of hyperbole, but not by much. In this stand alone episode we talk with Erik Klass, the entrepreneurial editor behind the submission service Submitit...