Today we tackle Jack Bickham’s Common Scene Errors, and boy, are there a lot of them, 14 to be precise. According to Scene and Sequel, these simple problems will derail your scenes, rob them of their impact and drag down your novel. We go through each error, identifying if they’re a problem in our own writing and discuss Bickham’s solution.

And because we’re not as prescriptive as Bickham, we begin the podcast interviewing three authors about their outlining process, perhaps one will be right for you.

Want to hear more of our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast, SnarkNotes, and detailed write up of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

The Writing Activity

Let’s pick one of the common errors we feel apply to our work and use his suggestion to fix it.

This Episode's Interviews

Inspired by Bickham’s note card strategy, we decided to see how other authors plan, outline (or not) their books.

Sheila Sullivan

Shelia Sullivan writes murder mysteries with a wry sense of humor. Her protagonists represent the full spectrum of women in our society and explores their different relationships. She just published Shadows, book three in her F.O.K. series. You can buy it here.

Janie Franz

Janie Franz has written numerous features and articles on a broad range of topics, including The Ultimate Wedding Reception Book which she co-wrote with a Texas DJ. She has written 12 novels that will soon be re-released through her new publishers. Her latest book in the Allen Rodriguez Investigation Mysteries series, Handful of Dirt, came out last December. You can purchase your copy here.

Annmarie Boyle

Annmarie Boyle fills her award-winning contemporary romance series, The Storyhill Musicians, with secret crushes, impulsive hookups, contentious partnerships, second-chance romances, sexual chemistry and happy endings. You can buy her latest book, Off the Record.

Bickham's 14 Common Errors in Scenes

14…dang. That’s quite a few. Don’t feel bad. Errors are kinda like Zodiac signs. Everyone’s got one (probably more than one). But don’t despair! Mercury might be in retrograde but if Bickham rarely finds more than one error or two in most writers’ stars.

Below, you’ll find a list of Bickham’s Common Scene Errors. We included a description and solution for a few of them, but you can find the complete explanation of each error and ways to fix them on our Patreon site.

- Too Many Characters in a Scene

- Circularity of Argument

- Unwanted Interruptions

- Getting off Track

- Inadvertent Summary

- Loss of Viewpoint

- Forgotten Scene Goal

- Unmotivated Opposition

- Illogical Disagreement

- Unfair Odds

- Overblown Internalizations

- Not Enough at Stake

- Inadvertent Red Herrings

- Phony, Contrived Disasters

1. Too Many Characters in a Scene, AKA The Party Animal

So your Scene threw a house party while its parents were out of town and the whole school showed up. There’s barf in your mom’s antique vase and vodka in the hot tub. You try to get a beer and mingle, but you can’t get a word in because everyone’s talking all at once.

Solution: Bickham says to turn down the music and whittle down the conflict to just your protagonist and one other person. Neighbors calling the cops might work too.

3. Unwanted Interruptions, AKA The Interrupter

In real life, people interrupt conversations all the–HEY! Fiction isn’t real life, remember. It won’t make the story more realistic if characters or explosions or screaming children or suspiciously timed knocks at the door continually cut characters off.

Solution: Stick to Causes & Effects. In that order.

13. Inadvertent Red Herrings, AKA The Chekhov

Don’t make the mistake of thinking your reader isn’t paying attention.

Solution:

“One must never place a loaded rifle on the stage if it isn’t going to go off. It’s wrong to make promises you don’t mean to keep.”

-Anton Chekhov

Continuing the Conversation: Rule Breakers

Adverb Allergies

Adverbs. We’re told to avoid them. It’s lazy writing, we’re warned. Adverbs don’t show, they tell, like a fifty fifty ratio of cake to frosting. It just isn’t right (and even illegal in some states). But how much do they detract to the quality of the writing?

Well adverbs certainly didn’t stop the Booker Prize Committee from awarding the prestigious award to John Banville’s The Sea.

Check out these sentences from Banville’s book, both containing two adverbs each:

There I was, suddenly, with a girl in my arms, figuratively, at least, doing the things that grown-ups did, holding her hand, and kissing her in the dark, and, when the picture had ended, standing aside, clearing my throat in grave politeness, to allow her to pass ahead of me under the heavy curtain and through the doorway out into the rain-washed sunlight of the summer evening.

Or this passage:

I felt inexplicably lightened; it was as if the evening, in all the drench and drip of its fallacious pathos, had temporarily taken over from me the burden of grieving.”

So why are adverbs (at least ‘overusing’ them) such a bad thing? This “rule” is usually attributed to Stephen King from his rant in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft.

In other words, he’s famous and successful and writers trust him. But if Gardner taught us anything, it’s that rigid rules and formulas doesn’t necessarily make good art.

Word Choices Be Damned

“Deep down, literary critics are nice people,,” said no one ever. Certainly not Keats. I mean he was dead for 72 years by the time literary critic, Robert Bridges, criticized the supposed “artificial” language in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale.” Bridges cited the word “forlorn” as proof of Keats’ bad taste. That and the fact that the poet rhymed “elf” with “self.”

Forlorn! the very word is like a bellTo toll me back from thee to my sole self!Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so wellAs she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fadesPast the near meadows, over the still stream,Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deepIn the next valley-glades:Was it a vision, or a waking dream?Fled is that music:—Do I wake or sleep?-John Keats, “Ode to a Nightingale”

As a creative writing teacher, I’ve read my fair share of bad poetry. Forced rhyme. Cliches. Emotional baggage in verse. But Bridges’ assessment seems rather harsh.

“The introduction, too, of the last stanza is artificial, while his [Keats] choosing elf to rhyme to self* turns out disastrously.”

By artificial, I’m guessing Bridges meant that “elf” and “self” and “forlorn” sound forced. Like a forced rhyme or awkward phrase. Perhaps tacky, the rhymes low hanging word choice fruit. Sure, “forlorn” does sound a bit clunky. Then again, Keats does liken it to a tolling bell: for-lorn/for-lorn. You can’t help but sway when you read it. Then you realize he knows he’s dying (his time is up) and the bell is tolling. But “disastrously?” With no follow up or explanation? Rude AF.

The Comma Splicer Supreme

Unlike the previous “errors,” this author utilizes actual grammatical errors, not the supposed bad taste storytelling kind. Charles Dickens, apparently, reigns supreme with his comma splices.

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair…”

WTF’s a Comma Splice? It’s when a writer tries to join two independent clauses with a comma. To fix this error, Dickens would have to include a coordinating or subordinating conjunction, a semi-colon or a period between the clauses. I don’t know about you, but “It was the best of times and it was the worse of times. Although it was the age of wisdom, it was also the age of foolishness; it was the epoch of incredulity…” just doesn’t read as well as the original.

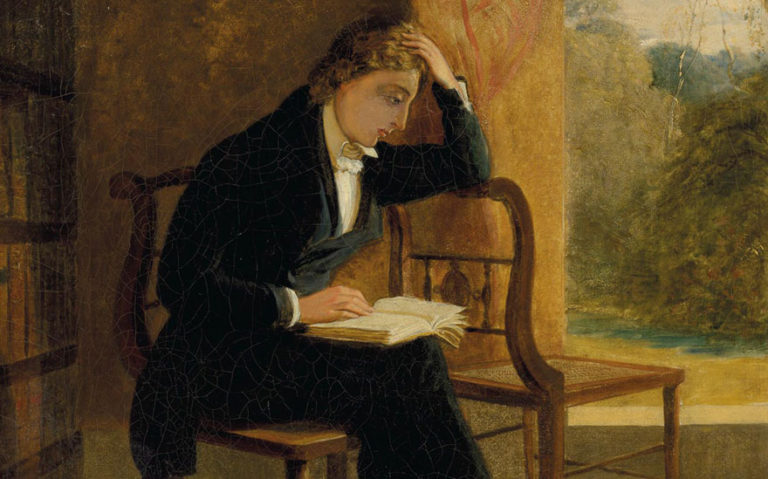

Tribute: John Keats

John Keats (1795 – 1821) is one of the most popular poets of the Western world despite having such a short life of only 25 years. Firmly dedicated to his poetry, he left medical school to pursue his dreams of being a poet. Some of his most famous poems were his Odes, such as Ode to a Nightingale, Ode to a Grecian Urn. His themes included nature, art, and mortality. Many of Keats’ later poems were written while he was dying of Tuberculosis, notably Ode to a Nightingale and most scholars attribute some of his genius with that morbid fact.

Keats was close friends with the famous Romantic writers, Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley. Shelley even wrote Keats’ elegy: Adonais: An Elegy on the Death of John Keats, Author of Endymion, Hyperion, etc. Two years later (1822), Percy Shelley drowned after his boat capsized. When Shelley’s body washed up on shore, copies of Keats’ poems were found in his coat pocket.

Keats is one of Renee’s favorite poets of all time. He is one of the biggest inspirations for pursuing poetry.

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...