After 70 pages of Jack Bickham’s Scene and Structure we feel we’ve got a pretty good handle on how to break our stories down into action-packed, disaster-ending scenes and the more contemplative internal sequels that hold the book together. What we’ve had a harder time with is finding these scene-sequel sequences in the books we own.

So, what gives, Bickham?

Apparently, there are multiple variations – in chapter nine, Bickham gives us ten options — to make one’s scene and sequel not so obvious. In this episode, we’ll go depth on two of these techniques: the scene-within-a-scene and imbedding a flashback within a sequel (which Renee then applies to section in her memoir.)

We were interviewed on Who Makes a Podcast!

Hello Dear Listener! Check out our interview with Chris Cookley from Who Makes a Podcast, a platform dedicated to the people who make podcasts, and who want to make a podcast. Listen in to Chris Cookley interview Kim and Renee about how we craft an episode of Words to Write by! Also, for podcasting enthusiasts and creators, we highly encourage you to check out his other amazing episodes.

Join Us at the Women's National Book Association!

Hello, Dear Writers! Have you ever considered using podcasting to promote your work and brand as an author? Join Kim and Renee at a Virtual Lunch & Learn at the Women’s National Book Association on November 10th from 12:00 – 1:00pm! They’ll discuss how authors can reach news audiences and expand their platforms, which can be as simple as being interviewed on other people’s podcasts or as elaborate as creating your own.

To attend, become a member of the Women’s National Book Association.

Variations in Structure

In this chapter, Bickham lists the ways a writer can vary the structure of scenes and sequels.

An Outlining Method

Bickham advises, however, before going wild with these techniques, that a writer “should plan your story originally in classic scenes and sequels, arranged in the classic strait sequential pattern, with nothing skipped anywhere and no part of anything out of its normal order.”

Fictional crime novelist, Harlan Thrombey’s (played by Christopher Plummer) desk in Knives Out.

Bickham claims some novels or page-turner novels religiously follow a scene/sequel structure. On the episode, Renee and Kim were not so convinced.

Have you found that follows Bickham’s rigid scene/sequel rules in the wild? Post them on our Community Forum.

Variations in Scene Structure

Wait, What's in a Scene again?

You! Yes, you there, hunched over that screen swilling Mountain Dew! Get to that board and write me the three elements of a scene!

Ok, Punishment Over. Let's Break Some More Rules

- Your protagonist doesn’t have to announce the scene goal if the scene goal is obvious.

- If your reader knows of a plot going on behind the protagonist’s back, a scene may lack a full blown disaster, especially if the scene’s purpose is to lead or position the viewpoint character to their doom.

- Insert a scene within a scene. Check out our bonus episode in which Kim applies this variation in her Fantasy novel. In this episode, Kim reads from Hemmingway’s “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” to illustrate how an author embeds scenes within a scene.

- Weave sequels throughout your scenes.

- Write the scene structure: goal, conflict, disaster, out of the usual order.

Variations in Sequel Structure

Stop! The writer who attempteth these Variations in Sequel Structure must answer us this question exactly, ere the followeth vairations shall confuse thee.

Aaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!!!!!!!

So What is the Air-speed Velocity of an Unladen Sequel?

- Delete or reduce sequel components (emotion, thought, plan, action) to just a word or phrase.

- Some sequel components can much longer or shorter than others.

- Re-arrange the order of sequel components.

- A scene can pause a sequel.

- Your protagonist can “think” or remember in scenes (i.e., a flashback). Below is an example of a scene within a sequel from Flanner O’Connor’s short story, Good Country People (also one of Renee’s favorites of all time). The scene is part of the ‘thoughts’ the mother has about her daughter, whose education and PhD makes her smart, but with no common sense:

Whenever she looked at Joy this way, she could not help but feel that it would have been better if the child had not taken the Ph.D. It had certainly not brought her out any and now that she had it, there was no more excuse for her to go to school again. Mrs. Hopewell thought it was nice for girls to go to school to have a good time but Joy had “gone through.” Anyhow, she would not have been strong enough to go again. The doctors had told Mrs. Hopewell that with the best of care, Joy might see forty-five. She had a weak heart. Joy had made it plain that if it had not been for this condition, she would be far from these red hills and good country people. She would be in a university lecturing to people who knew what she was talking about. And Mrs. Hopewell could very well picture her there, looking like a scarecrow and lecturing to more of the same. Here she went about all day in a six-year-old skirt and a yellow sweat shirt with a faded cowboy on a horse embossed on it. She thought this was funny; Mrs. Hopewell thought it was idiotic and showed simply that she was still a child. She was brilliant but she didn’t have a grain of sense. It seemed to Mrs. Hopewell that every year she grew less like other people and more like herself — bloated, rude, and squint-eyed. And she said such strange things! To her own mother she had said — without warning, without excuse, standing up in the middle of a meal with her face purple and her mouth halt full — “Woman! do you ever look inside? Do you ever look inside and see what you are _not_? God!” she had cried sinking down again and staring at her plate, “Malebranche was right: we are not our own light. We are not our own light!” Mrs. Hopewell had no idea to this day what brought that on. She had only made the remark, hoping Joy would take it in, that a smile never hurt anyone.

Continuing the Conversation: Nobel Prize in Literature

Nobel prizes aren’t just for scientists! There’s a category for Literature (and Peace). We’ve all heard of it, but what is it, exactly, and where did it come from? Alfred Nobel, a Swedish engineer who invented dynamite and the blasting cap, died in 1896 a very wealthy man (265 million in today’s standard). In his will, he asked that his fortune fund five awards (6 now) a year for those “who have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” Nobel was a reader and in his spare time wrote short stories and plays, which may explain why he created an award for a writer who “produced the most outstanding work in an idealistic direction.” This also explains why there is an award for literature, but not music (don’t get me started on Bob Dylan).

Winners of the Nobel Prize receive 10 million Swedish krona–(currently worth $882,300), an 18 karat gold commemorative coin and a nifty plaque.

Fun Fact: When Alfred’s brother Ludvig died from a heart attack in France. the French newspaper mistakenly thought it was Alfred who had died and not his brother. As a result, they wrote an obituary for Alfred Nobel. Almost a decade before his own death, Alfred got to read his own obituary, wherein he was named “the merchant of death.” So it seems the inventor of dynamite knew the impact his invention had in war and on suffering, hence (probably) his creation of a Peace category, for “the person who has done the most or best to advance fellowship among nations, the abolition or reduction of standing armies, and the establishment and promotion of peace congresses.”

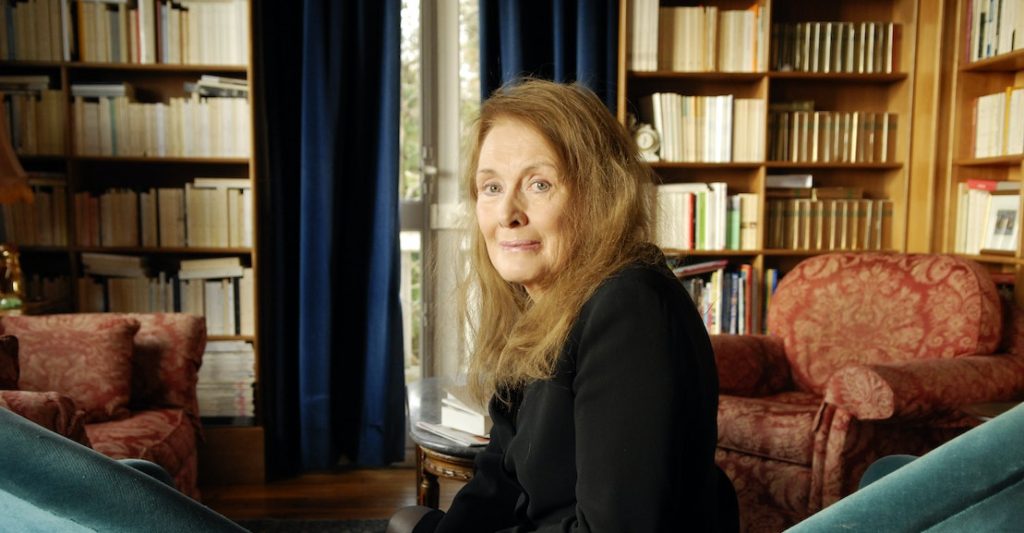

Tribute: Annie Ernaux

The French writer, Annie Ernaux, is the current holder of the Nobel Prize for Literature (2022) “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”. Born in 1940, she writes autobiographical fiction and memoir. She employs a variety of themes and experiences in her vast body of work (her family, her marriage, an affair, an abortion, breast cancer, death). Her most famous work, Les Années (The Years), is a memoir written in the third person, which spans time (past, present, and future) and genre. Other noteworthy books include: A Woman’s Story, I Remain in the Darkness, and The Possession. She is the 17th woman writer to be awarded the Nobel in Literature (102 have been given to men).

What’s Really Happening When AI Writes?

We've been putting AI chatbots through creative writing challenges, but what are these systems actually doing when they write? In this episode, we bring in AI expert Bill Moore....