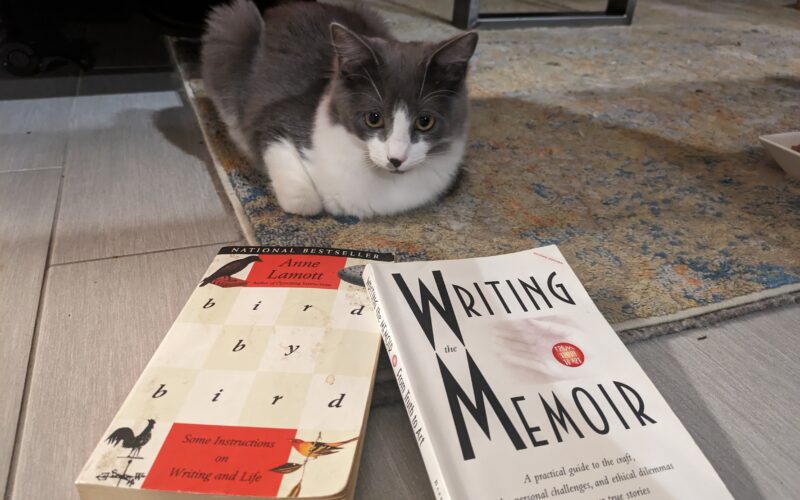

Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird

Chapters 9 & 10

We’re covering two different topics from Ann Lamott’s book Bird by Bird. First off is scene setting, both its importance for your characters and how to get all the details right (quick answer, ask an expert). Then we’re back to finding out what your story is about and how to return to a scene or chapter again and again (and again) until you can finally say, “Yes, that is how it needs to be written.”

Also, following up on last week’s episode about character verses plot driven stories, we talk to three genre writers about their approach.

Want to hear more about our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast, SnarkNotes, and detailed write up of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

This Episode's Interviews

In our last episode, we pitted the Character Driven approach to writing a novel to the Plot Driven. Does choosing one method produce quote unquote “Literature?” and the other its backwater cousin, Genre Fiction? Or is it a matter of using whatever tools a writer has on hand? Tune in!

Lia Riley

Lia Riley writes contempary romances and talks about K-drama (and other Korea pop culture) on her podcast Afternoona Delight. You can find her book, Upside Down, here.

Stuart Jaffe

Stuart Jaffe is the author of over 50 novels that mix pulp-adventure into contemporary science fiction and fantasy. Check out his Max Portal Paranormal Mystery series here.

Laura C. Stevenson

Laura C. Stevenson is an award-winning author of several young adult and mystery novels. You can get her post WWI mystery, All Men Glad and Wise here.

Set Design

We were divided on the usefulness of these short chapters. Full of meandering anecdotes, Set Design, as the title suggests, is all about setting in relation to characters. Renee believes it may be a sign of the diminishing returns to come (a phenomenon we’ve discovered at about the half way point of every writing advice book we’ve discussed). On the other hand, Kim, the trained journalist who conducts our awesome author interviews, really enjoyed Lamott’s suggestion to interview people who share your character’s identity, profession, likes and dislikes to get to know them.

Renee’s Rant: This chapter can be summed up in two sentences, which appear in the last paragraph:

- “I have asked all sorts of people to help me design sets.”

- “I try to imagine the movie set of this scene in as much detail as possible.”

This book may, indeed, be nearing its shelf life. Then again, we are at the halfway mark in the book. If we’ve learned anything from reading, discussing, and reviewing craft books, we know we’re about due for a lull in substance.

Kim’s Rave: Kim really enjoyed this chapter. She found Lamott scored on two important elements here:

- Some of what your character reveals to the world is both intentional and unintentional.

- Some are what we, as the author, want to reveal about the character and some are what the character wants to reveal about themselves.

Setting creates and showcases the psychological state revealing both the internal and external workings of the character. Just like in a real life interview! If, of course, the interviewer is tactful enough.

False Starts

You know… Ever feel like… What I mean is… Feeling stuck? Lamott uses a metaphor of the painter who paints over their canvas over and over again in the attempt to get it right. Much of the creative process includes deleting, trying again, attempting one thing and ending up somewhere unexpected. For Lamott, this included going to old folks homes and, through discovering a metaphor, finds they are more than just cliches.

Kim’s Rant: This chapter doesn’t sit well with Kim. For one thing, there’s Shitty First Drafts, which Lamott already covered in the beginning of the book. We remember Lamott tells us to keep moving forward, no matter how bad it is. Kim senses inconsistency here. So which is it, Lamott? Keep going without editing or erase the slate and try again? Part of the Shitty First Draft is writing about a character you’re not going to use. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Renee’s Rave: The painter metaphor is apt, namely because it illustrates how Renee’s brain works. She’s a deleter, a reviser, a stress-ball of a writer… Renee lurks in the creative trenches of the unknown. Does she enjoy the process? F#*$ No. Lurking is rude and it creeps people out. But it’s worth the two and a half years (and social anxiety) it takes to find the right metaphor…right…?

Continuing the (Process) Conversation

The Process of False Starts

It’s kind of frightening not knowing when, how, or if your writing will pan out. I mean, we all know writing is hard. Duh. It’s a particularly painful process we’ve all come to know and even love. “Getting to know your character” and encountering “false starts” are all part of the process. Even Victor Hugo was once threatened with a fine from his publisher if he didn’t stop procrastinating and finish The Hunchback of Notre Dame. And poor George R. R. Martin has been writing Winds of Winter, the sixth book in the Game of Thrones series, for twelve years now. How do we relieve ourselves of such misery?

"The actual process, in my experience, is much more mysterious and more of a pain in the ass to discuss truthfully."

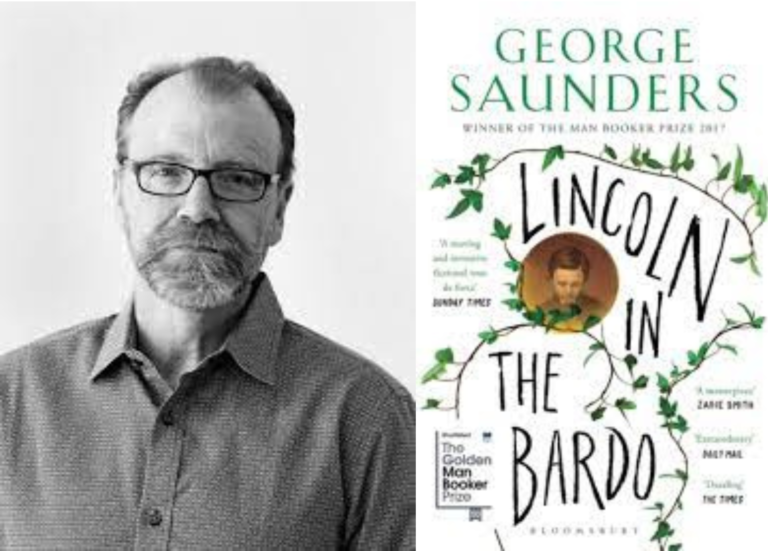

George Saunders is a well known professor and award winning author. His short stories, novels, and plays have won the National Magazine Award and was a finalist for the National Book Award. His novel, Lincoln in the Bardo, won the Booker Prize in 2017. In this interview, later published in the Guardian, Saunders discusses the creative process in terms of false starts. Essentially, artists’ expectations versus their creative reality: “an artist works outside the realm of strict logic. Simply knowing one’s intention and then executing it does not make good art.

The ‘creative model’ for Saunders isn’t the plotting, planning, executing linear approach young writers often believe famous authors use to pen great works. Saunders approach revolves around doing the work, “the sort of magic antidote always is labor. You know you work work work work, and in time your natural, you know, kind of human stupidity will cave in, and this artistic vastness will come in to help you out.” In other words, moving forward. Quantity really does produce quality.

You can watch a clip of Saunders’ interview for Granta Magazine during which he discusses the writing process below and read his article in the Guardian.

The Secret to Getting Your Short Stories Publish

Okay, maybe that's a bit of hyperbole, but not by much. In this stand alone episode we talk with Erik Klass, the entrepreneurial editor behind the submission service Submitit...