Chapter 1 & 2: Scene & Structure

In this podcast we give our first impressions of our new book, Jack Bickham’s Scene and Structure, and, being the enthusiastic students that we are, we begin by identifying his central thesis. Then it’s on to Chapter 2, in which we answer some novice novelist questions and discuss Bickham’s approach to a story’s first page. To further our understanding, Kim “Bickhamizes” the beginning of her new fantasy novel.

As a bonus, Renee has a special message for any former Borders employees who worked the late-night Harry Potter release parties back in the 90’s.

General Impressions

Unlike a lot of craft books dispensing general, vague, and even cliche-ic advice concerning the writing process (have you tried Morning Pages? How about meditation? Um….

Get lost, Nanowrimo! Bikham’s got appendices and line by line analysis of published work and he’s not afraid to use ’em!

Chapter One: The Structure of Modern Fiction

Structure as Process, Not Formula

We’ve all been warned about formulas and the hack writing that comes with it; however, Bikham argues structure and form aren’t rigid templates that turn writers into hacks or robots or robot-hacks:

A thorough understanding and uses of fiction’s classic structural patterns frees the writer from having to worry about the wrong things, and allows her to concentrate her imagination on characters and events.

In other words, a clear understanding of the foundation (Structure) and shape (Form) fiction takes will give you the freedom to tell the story you want to tell, to experiment and discover your characters and their journey.

Yes, Dear Writer, you’ll be free–free like a naked streaker through the UCSC campus celebrating the first rain–unburdened by both one’s parents and pesky marijuana laws.

Structure Vs. Form: What's the Dif?

Structure is the pattern, the base of a story’s elements. Form is shape, the style of the story. Bikham uses an apt analogy to discern the two. He likens it to building a house. All houses have the same structure, but there are different styles (ie: forms) of houses. No matter the type of house, they all have beams, doors, windows, and a roof.

Chapter Two: Strategy: How to Start your Story and How to End It

5 Novice Novelist Questions (say that 5 times fast...)

Bikham says novice novelists are “plagued” by the following questions:

- How long should my novel be?

- Where should I start my story?

- How and When should I end my story?

- Do I need a lot of subplots?

- Does it have to have a happy ending?

I Y'am What I Y'am: The Self Concept 💪

Bikham believes the answers to a Novice Novelist’s questions lies in the protagonist’s Self Concept. For a strong beginning, Bikham argues an author must reveal a protagonist’s Self Concept to the reader and then threaten it with Change, or an external force as soon as possible.

So what is the Self Concept? It’s how the character sees themselves. Their identity. The sense of who/what they are. And it provides the groundwork for the plot of your novel and the construct for both your novel’s gripping start and satisfying end.

For example, we all know Renee is a crazy cat lady (Self Concept). She has five dresses covered in both cat patterns and cat hair (it’s true, just ask her students) and her husband has threatened divorce if she tries to own more cats than she can hold. Despite the risks, she strategically goes to the PetSmart on cat adoption days. She is certain–completely and utterly–she will never own a dog.

But then…one day…

The Threat/External Factor (ie: The Threatening Change)

…A stray dog saves her derpy cat Ezra from getting run over by a car (Change/External Factor Threatening Self Concept). What if, while she’s googling the number for animal control, Ezra and the dog become fast friends, taking turns bathing one another in a cute montage complete with a soundtrack by Sarah Mclachlan? Then Renee’s husband comes home, takes the dog out back to play catch, and names him Max Jr. Is there room in Renee’s identity for (gulp) a dog after all? Can she? Will she allow the dog to become part of the family?

No. The answer is no. Absolutely not. And this, according to Abby, Renee’s other cat, is what makes this a happy ending.

The End.

Start as Close as you Can to the Action

Bikham says the trick is to grip the reader by creating a sense of immediate urgency in the first few paragraphs of the novel. He argues that “readers are fascinated and threatened by change in their real lives, and nothing else fascinates or threatens them so much in fiction.”

So, set up both the Self-Concept and the External Factor and go about waving it around menacingly in a dark alleyway with a knife in the very beginning of the novel.

Note how Bikham does not mention Plato’s sage advice to start In Mideas Res: In the middle of things. We’re often told to start our stories in the middle of something exciting, or at least in the middle of some kind of action appropriate to the story. But Bikham takes this advice a bit further, defining the kind of action one should start with: impending change. Show the character’s life is about to change and voila! Insta-Beginning-of-Novel.

Continuing the Discussion: History of The Novel (and its Structure)

The 18th C. Novel: Epistelary Structure

The form of the novel has definitely evolved since it appeared in the 18th Century. Although some debate exists as to who wrote the “first novel,” most scholars point to Samuel Richardson‘s Pamela; or A Virtue Rewarded. Written in 1740, Richardson wrote in epistolary form, a style other Novelists of the time adopted in an attempt to lend “truthiness” to the story. Before the Novel, if one wanted a long written story, they entertained themselves with Epic Poetry. Otherwise, book length prose was limited to non-fiction, such historical or opinion pieces. So, to ease readers into the new form, early novelists included Prologues claiming the work was non-fiction (wink/wink) and maybe even a short paragraph or two written by the protagonist, stating the text was not a work of fiction.

In a SERIES of Familiar Letters from a Beautiful Young Damsel, To her PARENTS. Now first Published In order to cultivate the Principles of Virtue and Religion in the Minds of the Youth of Both Sexes. A Narrative which has its Foundation in TRUTH and NATURE.

Samuel Richardson, Pamela

Early 18th C. Diary Structure

In keeping with the “truthy” style of fiction, some authors wrote from the point of view of the protagonist writing journal entries or a diary as a written account after the plot events had taken place. Robinson Crusoe (1719) by Daniel Defoe:

We were not much more than a quarter of an hour out of our ship till we saw her sink, and then I understood for the first time what was meant by a ship foundering in the sea. I must acknowledge I had hardly eyes to look up when the seamen told me she was sinking; for from the moment that they rather put me into the boat than that I might be said to go in, my heart was, as it were, dead within me, partly with fright, partly with horror of mind, and the thoughts of what was yet before me.

Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe

19th C. 3rd Person Omniscient with Immediacy in Time

Then, a shift occurred in both style and point of view. Authors shed the limitations of diary entries and letters and allowed the the plot events to unfold in real time (as in the events happen as one reads) and told in third person omniscient — the god-like narrator knows all. Although a Christmas Carol (1843) does technically start in the first person, Dickens adopts the third person point of view throughout most of the text:

They went, the Ghost and Scrooge, across the hall, to a door at the back of the house. It opened before them, and disclosed a long, bare, melancholy room, made barer still by lines of plain deal forms and desks. At one of these a lonely boy was reading near a feeble fire; and Scrooge sat down upon a form, and wept to see his poor forgotten self as he used to be.

Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

20th C. 3rd Person Limited

Maintaining the flow of immediate narrative time, authors then closed the narrative distance and adopted the third person limited. At this point, the Novel now resembles the most popular form in the Contemporary Novel. Here’s an example from The Call of the Wild (1903) by Jack London. Not only did he tell the story from a limited point of view, but limited it to Buck’s (a dog’s) perspective:

In a flash Buck knew it. The time had come. It was to the death. As they circled about, snarling, ears laid back, keenly watchful for the advantage, the scene came to Buck with a sense of familiarity. He seemed to remember it all,—the white woods, and earth, and moonlight, and the thrill of battle. Over the whiteness and silence brooded a ghostly calm. There was not the faintest whisper of air—nothing moved, not a leaf quivered, the visible breaths of the dogs rising slowly and lingering in the frosty air. They had made short work of the snowshoe rabbit, these dogs that were ill-tamed wolves; and they were now drawn up in an expectant circle. They, too, were silent, their eyes only gleaming and their breaths drifting slowly upward. To Buck it was nothing new or strange, this scene of old time. It was as though it had always been, the wonted way of things.

Jack London, Call of the Wild

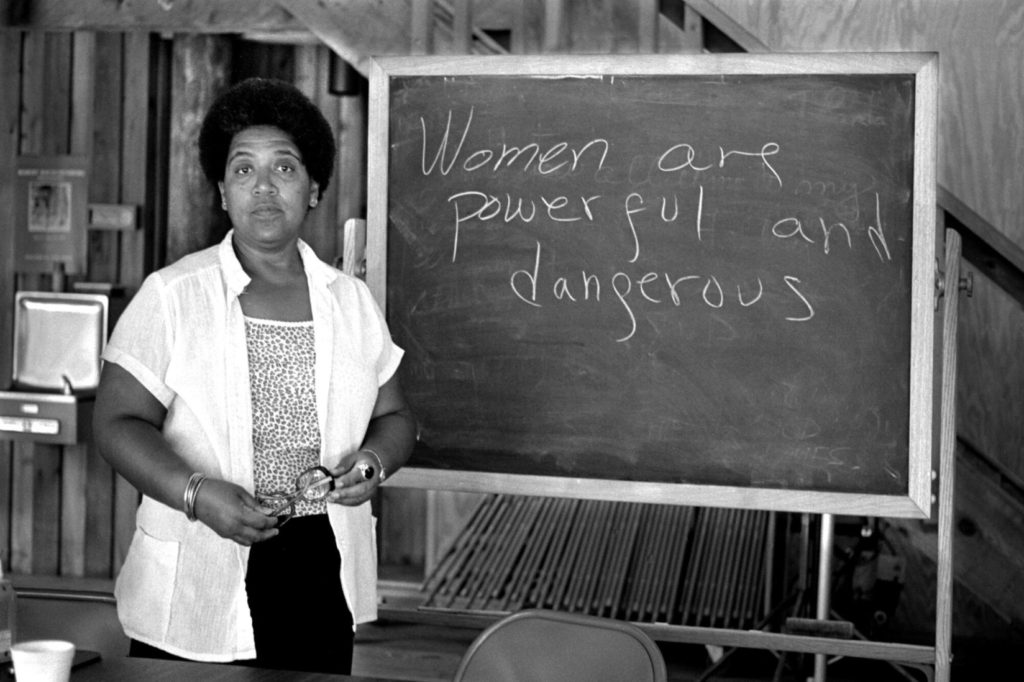

A Tribute to Audre Lorde

You won’t find Audre Lorde mentioned in Scene & Structure. However, we at Words to Write by want to dedicate this episode Audre Lorde, a champion of civil rights, who fought for black folks, the LGBTQ community, and women in her poetry. Audre Lorde (1934 – 1992), born of West Indian immigrants, was a poet, spoken word artist, novelist and essayist whose work explores, among other things, otherness in identity, sexuality, and race; specifically, she deconstructed and challenged the rigid definition and distinction between the genders. She was a poet-in-residence at Taugaloo College, during which she founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press. One of her most famous, and aptly named essays was titled: “The Master’s Tools Will Not Dismantle the Master’s House.” In 1988, she won the National Book Award for her essay collection, A Burst of Light. She was the poet Laureate of New York (1991 – 1992).

What’s Really Happening When AI Writes?

We've been putting AI chatbots through creative writing challenges, but what are these systems actually doing when they write? In this episode, we bring in AI expert Bill Moore....