Chapter 3 - Scene & Structure

This episode is all about cause and effect, what it is, why it is critical in fiction despite being largely absent in real life, and how it works line by line as stimulus and response. In chapter 3 of his book Scene & Structure, Jack Bickham has some hard rules about applying and ordering stimulus, internalization, and response. We examine our own writing to see if it follows the proscribed format.

And, as a bonus, we start the episode off with interviews we did at the San Francisco Writers Conference that we’re calling “Confessions of Craft Book Addicts.”

Cause & Effect (or, you don't need a science degree to write fiction)

In this chapter, Bikham introduces the physics of story: the cause and effect. Cause is striking the match, effect is the fire. Used properly, they create a believable set of events for the reader. (Guess what definitions are going on this week’s test?)

Effects: plot developments (ie: stuff that happens in your story).

Causes: background (ie: what sets the effects in motion).

By revealing reasons for your character’s reactions to story elements and maintaining the cause and effect order, you create a story with a believable set of events and not just a series of unrelated things that happen.

Real Life vs Fiction (or, why Renee's out of vodka)

For readers, causes and in turn effects help the events of the story make sense (indeed, if Renee had a dollar for every student whose told her “I know it doesn’t make sense but that’s how it really happened!” she could finally afford her college’s health care insurance). But in a story, events need causes and characters need reasons for acting the way they do in response.

I suspect that when you write a story that makes sense through use of cause and effect, you are also implying, somehow, that life is worth living.

-Jack Bikham

In other words, the story gods are merciful; events in a story happen for a reason. Isn’t that nice.

Stimulus & Response (or, Pavlov FTW)

Bikham makes a distinction between cause and effect and stimulus and response, which is “cause and effect made more specific” (Bikham).

Yes, dear writer, even readers need treats.

Stimulus: Event, dialogue, or action that sets the character in motion. Note – this is external.

Response: the character’s reaction to the stimulus.

On this week’s episode, Kim illustrates stimulus and response with Hitchhiker’s guide to the Galaxy, a ridiculous romp through space, as an example. Even though the main character survives the demolition of Earth and the second worst poetry in the galaxy, all in a bath towel, Adams’ still maintains the “gravity” of events through stimulus and response.

Internalization & Background (or, why Walking Dead sucks now)

Background: an explanation of a stimulus or response so it makes sense why it happened.

Internalization: the thoughts and feelings of a character before they respond to the stimulus, which explains the response they’re going to have.

Micro-cosom in Action: Jack London's Call of the Wild

Renee diagrammed a scene from Call of the Wild to illustrate how cause and effect works in a story in terms of stimulus, response, internalization, and background.

But Spitz, cold and calculating even in his supreme moods (background for later stimulus), left the pack and cut across a narrow neck of land where the creek made a long bend around (stimulus). Buck did not know of this (background for later response), and as he rounded the bend, the frost wraith of a rabbit still flitting before him, he saw another and larger frost wraith leap from the overhanging bank into the immediate path of the rabbit (stimulus). It was Spitz. Buck did not cry out (response). He did not check himself, but drove in upon Spitz, shoulder to shoulder (more response), so hard that he missed the throat (background/justification). They rolled over and over in the powdery snow (stimulus).

Continuing the Conversation: Experimental Novel Forms

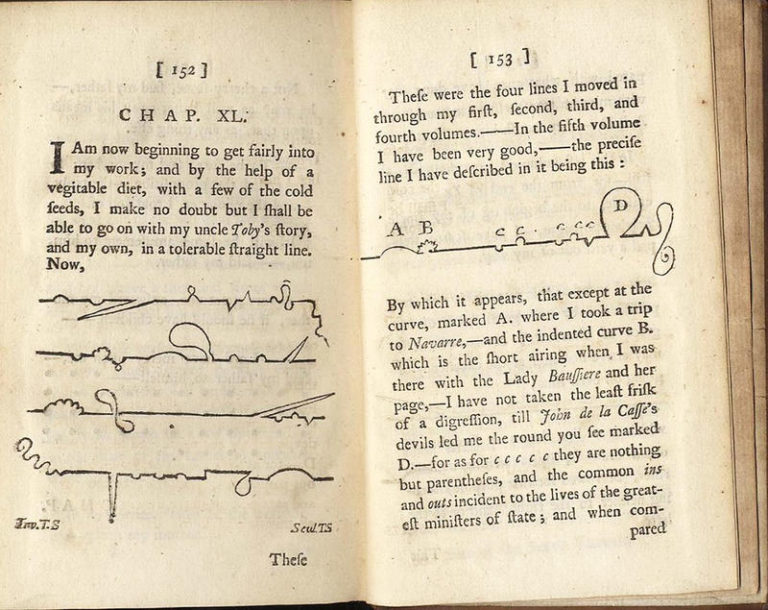

Although cause and effect are basic structures of scene and story, how an author tackles the physics of a story can be experimental and radical in scope. The first experimental novel, according to scholars, was Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy (1759). Inspired by the metaphysical poets and John Locke’s essays, Sterne turned narrative on its head with graphics (a full black page to show mourning for the death of a character) and extensive backgrounds and internalizations (readers don’t even learn the main character’s backstory until the third volume). The story spans nine volumes.

In 1910 – 1920, the beginning of the Modernist movement, experimental forms flourished. During this period, we get James Joyce’s Ulysses, Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, and T.S. Eliot’s prose and poetry. Just like in Absurdist plays, novelists from other literary movements, such as Dadaist and Surrealist, pushed the novel’s narrative boundaries. One such author, F.T. Marinetti, wrote a novel as a “sound poem” called Zang Tumb Tumb.

In the twenty first century, new forms, such as electronic literature, have emerged, namely Patricia Lockwood’s novel, No One is Talking About This. Composed entirely on an iPhone, the novel utilizes hypertext and code.

A Tribute: Douglass Adams

Douglas Adams (1952 – 2001) was a British science fiction author, essayist, and radio drama producer. His most famous work, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (also a favorite of Kim and Renee), started as a BBC radio comedy but was later developed into a “trilogy” of six books. Famous for his humor and wit, he even wrote a sketch for Monty Python’s Flying Circus and three episodes of Doctor Who. A champion of the environment, he once hiked Mt Kilimanjaro in a rhino suit for charity. Richard Dawkins dedicated The God Delusion to Adams, who once proclaimed himself a “radical atheist” because he “really meant it.”

What’s Really Happening When AI Writes?

We've been putting AI chatbots through creative writing challenges, but what are these systems actually doing when they write? In this episode, we bring in AI expert Bill Moore....