Christopher Vogler's The Writer's Journey

Stage One: The Ordinary World

If you have read even just the first part of a blog post on the Hero’s Journey, you know the hero starts off in the Ordinary World before embarking on their epic adventure. But the Ordinary World is more than a boring place the hero is itching to leave.

According to Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writer’s Journey, there’s a lot of that needs to be included in the Ordinary World section of the story. The writer must establish an interesting and sympathetic main character, set the mood and expectations, establish what’s at stake, and squeeze in backstory (using graceful exposition) and theme.

That’s a lot to unpack, but we somehow manage in this podcast episode! There are many, many more subheadings in this very loooong chapter, but as we point out, most don’t need to be there.

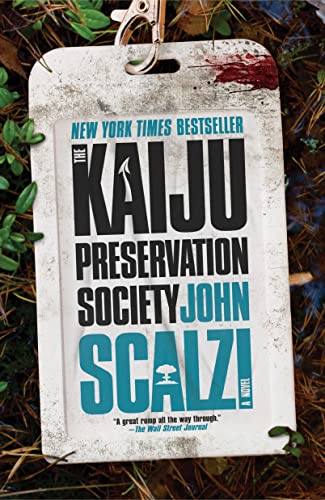

Vogler finishes up the chapter with examples from The Wizard of Oz (the movie, not the book), but rather than rehash that, we picked a better book: John Scalzi’s Kaiju Preservation Society and boy does it ever have on heck of an ordinary world for the hero to leave behind.

Our Novel Approach to The Writer's Journey

We’ve chosen four novels to analyze while we read Vogler’s book, which will serve as examples to help you on your own journey to writing a novel based on the Hero’s Journey. Here’s what Kim & Renee are reading:

Goodbye Archetypes! Hello The Ordinary World!

Now that we’ve survived the Archetypes, we’re onto the plot elements of the Hero’s Journey. If you haven’t been listening or paying attention to our Snark Notes thus far (really? this is the episode you decided to start with?), we’ve begun analyzing John Scalzi’s Kaiju Preservation Society as it pertains to Vogler’s Hero’s Journey. We’ve only read chapter one, so you still have time to get the book and get started before the next episode.

The Hero's Journey as per Kaiju Preservation Society

When COVID-19 sweeps through New York City, Jamie Gray is stuck as a dead-end driver for food delivery apps. That is, until Jamie makes a delivery to an old acquaintance, Tom, who works at what he calls “an animal rights organization.” Tom’s team needs a last-minute grunt to handle things on their next field visit. Jamie, eager to do anything, immediately signs on.

What Tom doesn’t tell Jamie is that the animals his team cares for are not here on Earth. Not our Earth, at least. In an alternate dimension, massive dinosaur-like creatures named Kaiju roam a warm and human-free world. They’re the universe’s largest and most dangerous panda and they’re in trouble.

It’s not just the Kaiju Preservation Society that’s found its way to the alternate world. Others have, too–and their carelessness could cause millions back on our Earth to die.

If you’ve listened to this episode, you know the the organization of this book left us quite incensed (and Renee drunk). Thank goodness for Snark Notes! Below we wade through Vogler’s muck and find the gems. Again, you’re welcome. Don’t forget, 2 Buck Chuck isn’t $2 anymore. Learn more about how you can help Renee keep Charles Shaw in business.

The Opening Image

All The Heavy Lifting

The first few chapters of your novel have a lot of work to do. The Ordinary World prepares the reader not just what the Protagonist’s “normal” looks like, but the nature of the Threshold into the Special World in Act II. Vogler begins with a clear enough thesis. Much like the intellectually vapid 5 Paragraph Essays y’all wrote in High School, he delivers four (surprisingly strong) guiding principles for the start of a story. On the podcast, we realize the Opening Scene in Game of Thrones ticked every single one of Vogler’s principles below:

“The story must hook the reader or viewer, set the tone of the story, suggest where it’s going, and get across a mass of information without slowing the pace.”

1. How to Hook the Reader (and Other Creative Choices Out of the Author's Control)

Vogler reminds us that we really do read a book (or watch a movie) by its cover (or movie poster). Titles, he says, should be metaphorical, hinting to the themes and plot in the book/film. Martin’s Game of Thrones is a riff off of the real life War of the Roses, which refers to the British Monarchy offing themselves to win the throne.

Unfortunately, titles and cover art aren’t always within the author’s control. That doesn’t mean it’s not valuable to create one anyway! For inspiration, Kim commissioned an artist to draw portraits of the characters in her Boy Bands & Dragons novel series, which you can see here. Although Our Comeback Tour is Slaying Monsters isn’t exactly a metaphor. . .

Kaiju Preservation Society. The title says it all: it will be about a Society/Organization which Protects Kaijus. Paired with an employee badge smeared in blood, this book invokes some serious Jurassic Park Vibes. IMO, Scalzi gets five stars for title and presentation.

2. HOW TO SET THE TONE!!!

According to Vogler, the writer should set the Tone – a rather nebulous term which, for the sake of novels at least, usually means “mood” – in the Opening Image, which may visually hint at the “Special World of Act Two.” All well and good if you’re writing a movie, which is limited to sight and sound. But what if you’re writing a novel? We’re glad you asked.

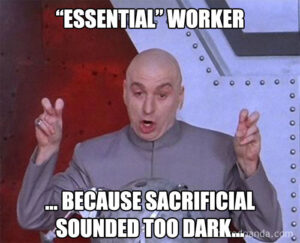

Boss’ Office @ FudMud. Scalzi sets his story at the start of the Pandemic, which grounds any reader (at least for the next decade) in a shared time, place, and tone of collective dread we’ve come to know and not love. In the first chapter, not only does the main character get fired from his cushy start up job, but he’s reduced to becoming a “deliverator,” a gig delivery driver for the very company who sacked him so he can pay the rent.

Your Opening Scene might even be a Prologue (think ubiquitous Star Wars opening scroll), which, according to Vogler, gives an “essential piece of backstory”, hints at the genre/type of film, and begins with “a bang.” Renee recently watched a theatrical re-release of Terminator (great movie, btw. Not a line of dialogue nor plot point wasted) and she would argue the Terminator’s Opening Image/Prologue does all the heavy narrative lifting Vogler claims it should:

The opening image sets quite the ominous tone. What better way to show the Human Race teeters on the brink than an AI controlled tank crushing a carpet of human skulls? And note the key words in the Prologue: “The machines rose from the ashes of the nuclear fire. Their war to exterminate mankind had raged for decades, but the final battle would not be fought in the future. It would be fought here, in our present. Tonight. . .” Sci-Fi, anyone? Besides, nothing grips the viewer more than Hyper-Violent 1984 R-Rated Post-Nuclear Robot Holocaust Sci Fi like gray scale filters, pink lasers, and a backdrop of explosions, amiright? If this doesn’t illustrate what Vogler thinks an opening image/prologue should do, then we would be wrong to think his examples are outdated.

But it does illustrate his principles for an opening image so it only proves our point about his examples. Terminator is the quintessential 80’s sci-fi action film. Cameron’s all like: You want explosions? We got explosions. You want killer robots hell bent on finishing what our own nuclear weapons started? Bomb away! Want it to star the manliest man who ever lived (and be contractually obligated to pose full frontal)? Hell’s yeah! But for better or worse, the film industry and narrative expectations have changed since then and for a 25th Anniversary Edition of The Writer’s Journey we expect a bit more.

3. Where We're Going, We Don't Need. . .Wait, No, We Actually Do Need GPS

So where are we going? The year 1984, LA, 1:52AM to be precise. The Terminator and Reese (John Conner’s father – sorry, spoilers) go into the past to battle it out over the future of Sarah Conner. How do we know that? Text on the screen. Duh: “Los Angeles 2029A.D.” Since we’re starting in the year 2029 (only 5 more to go before we’re knee deep in skulls!), it’s important to be clear what the time/date/place is before embarking on a quest involving time travel.

Professional Lifter @ KPS. Similarly, in Kaiju Preservation Society, Scalzi sets us up quickly. We know the time: The Pandemic. We know he’s suffering the fate of many during this time: Trying to pay rent with a low wage food delivery gig. When his friend offers him a job “lifting things” with a salary that can afford him not just rent, but enough to buy a whole house, he agrees sight unseen.

4. How to Info Dump Without, Y'know, Dumping Info

We’d argue trying to avoid Information Dumping is a genre fiction writer’s nightmare. Introducing the Ordinary World comes with challenges (but Vogler doesn’t tell us what those challenges might be or how to avoid them), which is why a lot of fantasy novels include a Map. If you’re writing Fantasy or Sci-Fi, you have your work cut out for you here.

Stage One: The Ordinary World

Why not just start in The Special World? Because, Silly, how would you know it’s special? This contrast between the Ordinary to the Special puts also the drama in the “dramatic change when the threshold his finally crossed.”

The Problems of the Special World are already present in the Ordinary World. Martin illustrates this beautifully in his opening scene, which shows there’s a hidden danger lurking just beyond the gates.

Forshadowing

Vogler says the Ordinary World could be a hint to the Special World, which he later calls Foreshadowing. Yes, we know it was mentioned earlier, but it’s what he does in this chapter. Foreshadowing, which is like a mini version of what’s going to happen later in the story, is prevalent in Heist films when the Protagonist goes on a hiring spree. Want some foreshadowing on Steroids? Try Fight Club.

Inner & Outer Problems

According to Vogler, Protagonists “need an inner problem, a personality flaw, or a moral dilemma to work out.” Although he rehashes tired craft writing advice (I guess if you’d never heard it, it would be new to you), he doesn’t bother to provide examples.

In Kaiju Preservation Society, the main character’s Inner Problem (so far, since we’ve only read chapter one) is to keep his community together (keep a roof over his and his roommate’s heads during a world wide pandemic). His Outer Problem, the means to do so. At least, so far. We’ve only analyzed the first chapter. Stay tuned for more on our next episode.

Introducing the Protagonist (If Only Books Had Actors)

What is your hero doing when they take the stage? Whatever they do in their first scene “should be a model of the hero’s characteristic attitude and the future problems or solutions that will result.” On the podcast, we thought Natasha’s Opening Scene in The Avengers is a perfect example.

If you’re making a movie, then you’ve got an actor to do the characterizing for you. Case in point: Different actors = different characters.

Funny enough, Vogler uncharacteristically includes an example from a novel, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer:

“Say – I’m going in a-swimming, I am. Don’t you wish you could? But of course you’d druther work – wouldn’t you? Course you would!”

Tom contemplated the boy a bit, and said: “What do you call work?”

“Why, ain’t that work?”

Tom resumed his whitewashing, and answered carelessly: “Well, maybe it is, and maybe it ain’t. All I know, is, it suits Tom Sawyer.”

“Oh come, now, you don’t mean to let on that you like it?”

The brush continued to move. “Like it? Well, I don’t see why I oughtn’t to like it. Does a boy get a chance to whitewash a fence every day?”

That put the thing in a new light. Ben stopped nibbling his apple. Tom swept his brush daintily back and forth – stepped back to note the effect – added a touch here and there – criticised the effect again – Ben watching every move and getting more and more interested, more and more absorbed. Presently he said:

“Say, Tom, let me whitewash a little.”

Mark Twain introduces Tom Sawyer playing a con against the other kids in the neighborhood, essentially tricking all of his friends into whitewashing a fence. This scene snapshots Tom as a trickster who thinks up clever ways to manipulate people to get his way, which is a theme throughout the book. Don’t worry, Tom’s hijinks aren’t malicious.

Torturing your Hero for Fun and Profit

Being an author is quite the sadistic profession. It’s not enough that we dangle our Hero’s desire just out of reach and try everything we can to prevent them from finishing their quests. No, we have to give them handicaps too. Whether you kill off their parents or make them an un-loveable monster-killing mutant, it’s not enough for us to just set them off on a quest. No, we have to make them suffer. Vogler provides a few ways to manipulate your character’s mental or physical health for fun and profit.

Hero's Lack

Aka, the Orphan. Vogler worked for Disney, so is well versed in the Dead Mother trope. Take something fundamental away in the Hero’s life, something that was once part of their being, like their mom or spouse, and you’ve given a space for the Hero to fill throughout their quest.

Tragic Flaws

So your Hero thinks he’s hot $#!+. Maybe he is. But that’s no fun. Let’s knock that Hero down a bit and drag him down to our level.

Wounded Heroes

This wound can be psychological: “rejection, betrayal, or disappointment” or physical: “visible, physical injury or a deep emotional wound.” Whichever you choose, your Hero will be deliciously EMO like a sparkly vampire or a depressed wino who can’t get over his divorce.

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...