Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird

Chapters 7 & 8

We’ve gotten to some hearty chapters in Ann Lamott’s book Bird by Bird. First up is plot, which “grows out of characters.” We discuss what this means and if it’s applicable to genre writing. Then we turn to dialogue, and how you distill intent from the rambling conversation of what people say while maintaining their unique voice.

Putting our writing chops to the test, Renee took a hilarious 3000 word monologue by the Afternoon Delight podcast ladies and condensed it down to 600. Definitely worth a listen before you go hiking to the top of Mt Washington.

Want to hear more of our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast and detailed write up of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

This Episode's Interviews

In our last episode, we discussed how to create likeable, relatable characters. Lamott says each character (and person) tends an emotional acre. We give our characters flaws, which paradoxically makes them more likeable. We know how Lamott builds her characters, so this week, we ask working writers to tell us their process for developing great characters. Enjoy!

Patricia Schultheis

Patricia Schultheis is an award-winning author whose writings have appeared in several literary magazines. Her short story collection, St. Bart’s Way, was the Washington Writers’ Publishing House Prize Winner in 2015, and a finalist for the Flannery O’Conner award in 2008. Her memoir A Balanced Life was published by All Things That Matter Press in 2018.

Paul Lubaczewski

Paul Lubaczewski’s numerous stories have been published in science fiction and horror magazines and anthologies. You can purchase Like a Ton of Bricks his humorous horror story, with aliens, cannibal killers and mad scientists here.

The Writing Exercise

Take a 3000 word transcript of a monologue or conversation and reduce it down to readable dialogue.

Plot

Does your character interact with the world or does the world interact with your character? From such a question is literary or genre fiction made. Given that Lamott writes literary fiction, she advises writers to start with a character. But if you’re writing page turning genre fiction, then Bickham’s your man.

Character Vs Plot Driven Novels

What’s the dif? Perhaps it’s more apt to ask: who, or what is behind your novel’s steering wheel? If your protagonist interacts with the world emotionally, from within, then the author is really just going along for the ride.

But if the author is steering through a world of dragons and spaceships, or toward a group of rugged outlaws or shirtless, Scottish man-candy, then the protagonist’s personal struggles (like heartbreak) become more generalized plot points.

There are, however, exceptions of course.

Our Favorite Character Driven Novels

Kim’s Favorites

- The Summer Book Tove Jansson

- Master and Margarita Mikhail Bulgakov

- Klara and the Sun Kazuo Ishiguro

- Handmaid’s Tale Margaret Atwood

- Poisonwood Bible Barbara Kingsolver

- Fates and Furies Lauren Groff

Our Favorite Plot Driven Novels

Kim’s Favorites

- The Golden Compass Philip Pullman

- Snowcrash Neil Stephenson

- To Say Nothing of the Dog Connie Willis

- World War Z Max Brooks

- Watchmen Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

- The Power Naomi Alderman

Dramaaaaaaaaaaa

But if you’re the ‘what do we want? STRUCTURE! And when do we want it? NOW!’ sort of writer, Lamott invokes the one size fits all As Seen On TV Magic Slicing Dicing Plot Device Three Act Structure.

Good ol’ Aristotle. The gift that keeps on givin’. Check out past show notes here and here for a refresher course (Brought to you by John Gardner).

Plotting (Mwahahahahahahahaha)

Lamott says there’s three types of climaxes: a killing, healing, or a domination. These can be either metaphorical or real or both. No matter which type (or a mix of them) you choose, your protagonist should undergo some sort of change. Or, Lamott states, “what is the point of the story?” And, oddly enough, she says the ending should invoke a “sense of inevitability” in the reader, which (what a coincidence) Bickham mentions as well.

Dialogue

Kim translated this quite aptly in the episode:

You’ve got a very edited and compact character in books. Whereas in real life people are messy. In other words, don’t reproduce your favorite character in fiction and put them in another setting. By going out in the world and observing people interacting with people, getting a feel for real, complex people, it’s going to strengthen your ability as a writer far more than reading a book where somebody has already laid out the character and the emotional acre they need for the story. If you only read dialogue in books, you’ll be missing what was edited out.

Thanks, Kim.

So Read that $#*T Out Loud

Purple Prose

Please refrain from illustrating your prose with verbiage of the sanctimonious kind. In other words, you can get a one way ticket to Bad Dialogue Land at the Purple Prose Station. Gardner, ironically, warned us of the same thing. We even did an activity with this one.

…in that dialogue in a novel has more in common with the movies. George R.R. Martin gives similar advice.

Continuing the (Process) Conversation

Subtext, What is it, Exactly? And Why Definitions Matter.

More from the Man, the Myth, the Legend...

"Subtext is horizontal instead of below the surface of the text"

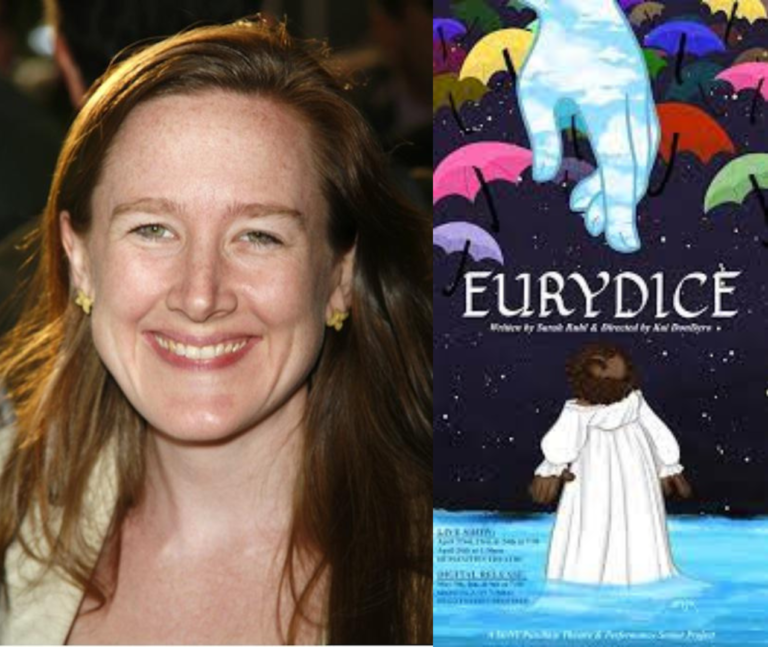

Sarah Ruhl is an award winning playwright and professor, recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship and PEN/Laura Pels International Foundation for Theater Award, and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama. She has written and directed plays for Broadway, such as Eurydice, In the Next Room (or the Vibrator Play), and The Clean House. She has also written the memoir, Smile: The Story of a Face.

In this interview for Concord Theatricals. She explains what subtext is not: “you’re not sort of saying one thing and then secretly thinking what are my real hidden feelings about that are in contradiction to what I’m saying,” but instead is “sincerely saying what I’m saying and feeling what I’m saying.”

So subtext is not just what’s not being says. It’s not a “secret” below the dialogue, she says. It’s “the design or what another character is doing at this moment in time.” In this sense, subtext is not a private matter for the character speaking, but a transactional exchange between other characters engaging in a conversation.

You can get her full interview and hear all of her awesome writing advice on the Concord Theatricals youtube channel.

Workshop: Naming Names in your Memoir

For this week’s workshop episode, Renee wrote about the brief time she spent as a child in Pacific Grove, CA, taking care to identify specific streets and locations as...