Every composition teacher will draw out a rising action graph on the board (yes, we’re old school). But how do you translate that diagram into the sentences and paragraphs that keep your readers engaged in your story?

In his book, Scene and Structure, Jack Bickham says to do it through structure (because of course he does), and gives seven different plot structures. Yes, dear listeners, we’re going through all of them, and, unlike Bickham, we give examples. Next we try to make sense of what is “backstory” and “hidden story” in a novel (or movie). And what about subplots? Everyone loves a good subplot, and we go over some tips on how to make them work in your novel.

But first up in the podcast, video game narratives! Find out what goes into the game that keeps you glued to the screen. We interview three professionals in the gaming industry on their approach to pacing.

The Writing Activity

Apply one of Bickham’s dramatic content tricks to your scene or sequel in order to keep your reader worried and reading.

This Episode's Interviews

So we’re learning loads about turning our novels into page turners, but what about stories that aren’t novels? What about videogames? Those of us who have played The Last of Us and Witcher 3 would agree: these games leave the player feeling just as emotionally invested in the story as we would reading a novel. However, the experience of playing versus reading just aren’t the same. This week we talk to narrative game designers about the storytelling–specifically pacing–techniques for video games (as opposed to novels).

Allison Salmon

Allison Salmon is a software engineer who’s been in the video games industry for about two decades. During that time, she’s worked on a wide range of games from the console game X-Men Origins: Wolverine to educational games to MagiQuest, an interactive game at the Great Wolf Lodge resorts. She’s currently a senior games engineer at Filament games and an instructor for University of California – Irvine.

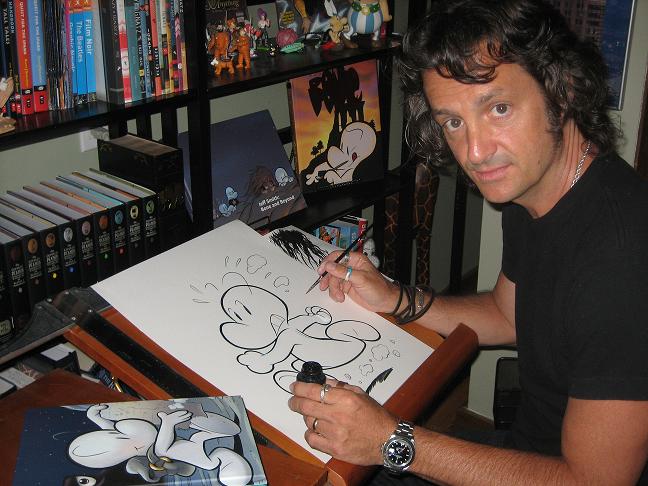

Lorenzo Pelosini

Lorenzo Pelosini is the author of the urban fantasy interactive graphic novels Demons of New York and Demons in High Heels. He published his first novel, Flight of the Hawk when he was 14 and has a degree in film from University Southern California School of Cinematic Arts. You can purchase his games here.

Lydia Symchych

Lydia Symchych (she/her) is a video game designer who’s helped create positive impact games including two bird-centric therapy games and People’s Pie, a government tax budgeting civics game. In 2022 she released a narrative game about a cozy day spent with a grandchild called I love you, X. You can play it here.

Plotting with Scene & Sequel

This chapter’s all about plotting, what Bickham calls Dramatic Principles. Essentially, he shows us how to keep the reader from getting bored by organizing scenes and sequels for optimum dramatic (and entertaining) effect.

Just as you build credible scenes by following the law of cause and effect in stimulus-and-response transactions, you build credible plots by linking scenes through the process of making one scene logically lead to the next via and linking sequel.

-Jack Bickham

For basic plot organization, Bickham doesn’t re-invent the wheel here; he adopts the traditional story arc, which means he advises you put your scenes in order of rising then (quickly) falling tension. Bickham then lays out all the dramatic plot templates you can use to play with your scenes and sequels to keep your reader reading.

We’ll give a quick overview below (like in the episode), but if you want a full explanation of each of Bickham’s principles, you’ll have to check out our SnarkNotes.

The So Close Yet So Far Plot

We all know your protagonist needs a goal. For this plot, however, each disaster takes them (seemingly) further and further away from said goal, not towards it. Then, at some point, they circle back or come upon it another way.

For example, in The Twin Towers when Sam and Frodo are at the Black Gate to Mordor, which took a whole movie and most of another to get to. They’re so close, yet…just as they’re about to sneak through the gate, Gollum convinces them to go “another way. A dark way.”

The Hijinks Ensue Plot

In this template, your disasters send the protagonist off on a crazy adventure that doesn’t seem to have anything to do with the goal, but in the end you realize it really is all connected. The disasters seem as random as if from a slot machine, which (Renee theorizes) tickles that part of the mammal brain that makes us love novelty (and slot machines and infinite scroll) so much. The key here is to not create a bunch of delays, but disasters that take the reader on a crazy and unexpected adventure, which, again, do somewhat logically lead to the story goal.

The Really Long Side Quest Plot

So this plot is a detour which derails the established adventure. The goal stays the same, but protagonist takes the long way around to get there. This template is most similar to the Hero’s Journey, mostly because by the end the hero returns to the starting point (and goal) of the story.

One obvious example is Dune (both film and novel). House Atreides arrives on Arrakis in order to control the Spice. Paul then goes on a really long adventure through the desert, becomes the Kwisatz Haderach, and gets to control the spice (nay, the universe).

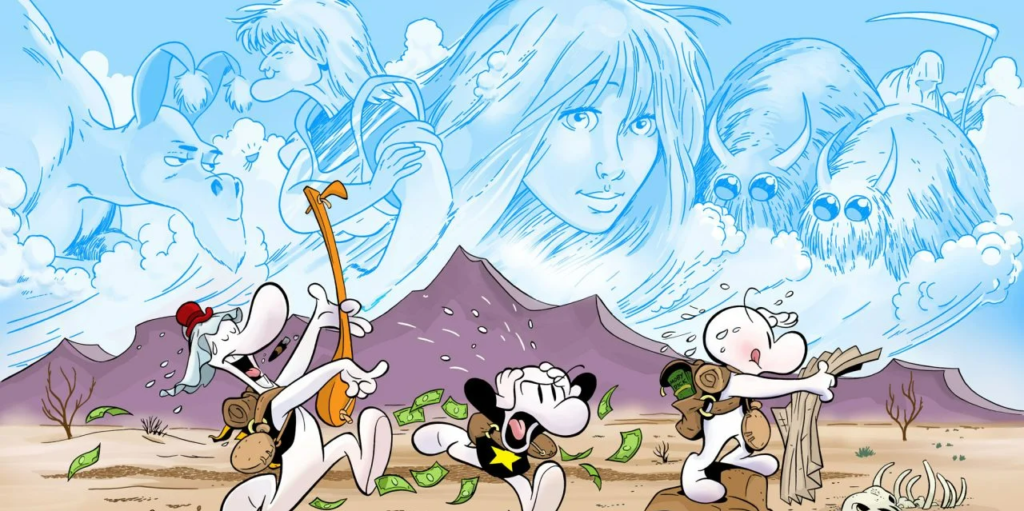

Then there’s Bone (thanks, Greg). Ok, so if you haven’t read Jeff Smith’s comic masterpiece, it’s time you start. This story also takes us on a really long side quest (it even takes a cartoon style into the world of another!). We’re talking a side quest of dragons and princesses and magic.

The Whose Story is It Anyway? Plot

This plot requires jumping chapter to chapter from multiple protagonists whose sub-plots add up to the larger story goal. Usually (Bickham is pretty adamant about this), the story revolves around one particular protagonist and always returns to the primary storyline. Examples include the following:

The Ticking Time Bomb Plot

There’s a time limit attached to this protagonist’s goal. By the end of the novel, the clock strikes twelve. Will they make it? You’ll have to turn the page to find out…

Examples of Hollywood Blockbuster plots abound with this one. Just think of every movie you’ve seen involving impending apocalypse. Or one involving an actual literal bomb about to go off.

But it need not be that nail biting Michael Bay two hour explosion-palooza…all you need is a ticking clock and the tension will follow.

The Disappearing Options Plot

The further we get through Bickham’s Scene & Structure, the more the amount of credible, specific examples seem to decrease. While impressed with appendices full of scenes not just from his own novels, but others, we’re beginning to see diminishing returns. Le Sigh. One might even call this phenomena a metaphor for the plot I’m describing.

In other words, whittle away your protagonist’s options until there’s nothing left but two miserable choice dregs left. No matter what your protagonist decides to do, they’re screwed and your readers reap the entertaining rewards.

Howl's Moving Castle

Howl’s Moving Castle is an example of the Disappearing Options plot. Literally–by the end of the story, there’s nothing left of Howl’s Castle but a platform with legs.

The It was (insert side character here) All Along Plot

Similar to the ticking time bomb only it’s a side character’s backstory that has impending consequences for the protagonist. In other words, a side character has been pulling the strings behind the scenes–such as a deep dark secret or hidden agenda–until their plans ‘go off’ at the end like a bomb.

Hollywood loves this plot. Keyser Söze from The Usual Suspects. Amy Elliot-Dunne from Gone Girl. Hugh Ransom Drysdale from Knives Out. Adrian Toomes (aka the Vulture) in Spiderman: Homecoming. Tyler Durden from Fight Club, etc.

There's More on Patreon

Bickham lays out some tricks you can use to manipulate scenes and sequels for dramatic effect. He reveals when to drop back into the story if you’ve cut the chapter mid scene or sequel. Plus more tricks. You can access the rest, with clear (yet snarky) explanation and examples, on our Patreon page.

Continuing the Conversation: Storytelling for Video Games

Novel writers seeking to write page turning novels have quite a bit in common with game developers creating stories that keep players playing. The key here is emotion, as in identifying emotionally with the protagonist, whether as a reader or a player.

“Each disaster puts your major viewpoint character deeper into trouble or seemingly farther from his story goal, then that character’s desperation and worry will intensify.”

-Jack Bickham

With each new quest, the player attaches themselves to the protagonist (sometimes formed with backstory). The player or reader identifies with the character’s goals and ultimate quest. Both readers and players align themselves emotionally with not so much what happens next, but what happens to the the protagonist they align with or play as.

Differences in Storytelling

As similar as a story in a game and a novel may seem, the differences between the reader experience and the player experience affect the way the story is told. Because the story in games rely on a transaction between the player and the game through HID (Human Interface Device) to be complete, the plots become simpler than in a novel.

How Players Experience Stories in Games

Conversations with NPCs

Like in a novel, the protagonist in a game (the player) witnesses events, chats with characters in the game, and interacts with their world to move the story along. Players have conversations with NPCs which reveals plots and level up the player, which allows them to access and move forward through the overarching plot.

Cut Scenes

In video games, players experience plot through cutscenes, which are mini movies that pause game play. In this sense, players become more like spectators of a film with an author in control of the storytelling experience. And, in the cut scene example from Last of Us below, designers embed these scenes to create deeper emotional connections to the protagonist and the story.

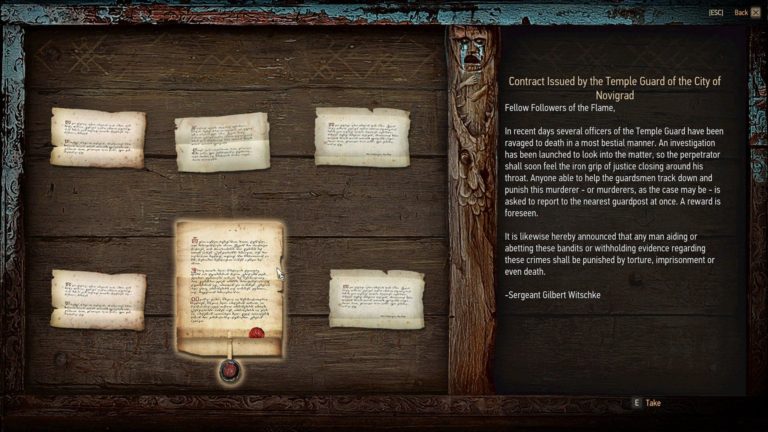

Primary Documents

More subtly, the player interacts with the narrative embedded in the world, usually through primary and secondary documents scattered throughout.

Four Primary Narrative Structures for Games

Similar to Dramatic Principle Plot Devices which keep readers reading, video games narrative devices utilize different dramatic principles to keep players playing. There are four primary narrative structures for games. Unlike a novel that follows around a protagonist, the key element here is perspective, which revolves around the player as the protagonist.

Linear Storytelling (such as Bioshock): This one is most similar to a reader’s role in a novel. As the player, you don’t have much choice in the plot developments–either in side or main quests–of the game. All choices on your journey funnel you to the same place: the final boss.

String of Pearls (such as Last of Us): There’s a bigger plot that ties all the other side quests together. Similar to Linear Storytelling, the main plot is fixed. As the player, you have some control but not a lot. As in Last of Us what happens will stay the same, but how you go about doing it and what you find is up to you as the player.

Branding or Branching Narrative (such as Witcher 3): Although there’s a main story quest plot in the background of the game, the choices the player makes will have an impact on the developments of the story. In other words, the player chooses different narrative branches depending on what they say or do during the game when a choice presents itself. It’s like a ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ novel; there’s a fixed number of options–and resulting plots–your character can take.

Amusement Park/Sandbox (World of Warcraft, Red Dead Redemption, Breath of the Wild): You have an entire map to explore. There’s hidden artifacts and minor side-quests dotting the landscape. Yes, there’s a looming antagonist or evil on the horizon, but it’ll take a while to armor and level up until you can beat the big bosses.

More Resources

Tribute: Jeff Smith

Continuing on our quest to draw attention to amazing stories, we’re dedicating our tribute this week to Jeff Smith (1960). Smith is the author of the acclaimed, award winning, and self-published series, Bone, which tells the art bending tale of the Bone cousins and their adventures. Smith drew from various inspirations to write the series, including Moby Dick, Huckleberry Finn, and Scrooge McDuck comics. He’s won ten Eisner Awards and eleven Harvey Awards, as well as the National Cartoonists Society’s award. He’s also the author of the RASL and Tuki comics.

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...