Anne Lamott's Bird by Bird

Chapters 11 & 12

Even published authors have problems getting the magical stories in their heads into finished manuscript. But Anne Lamott’s account of how, over the course of three years, she completely rewrote what would be her second novel several times, probably deserves a prize for perseverance (or stubbornness). In this podcast we discuss what was wrong with each of those drafts and the techniques she used to fix them. We even try her idea of writing a plot treatment for our own chapters.

Want to hear more of our exercise workshop? We post the bonus podcast, SnarkNotes, and detailed write up of the exercises on our Words to Write by Patreon account.

This Episode's Interviews

In our last episode, we discussed Lamott’s advice to interview people who can help you in the Set Design of your novel. For this episode, we have an interview with Catherina Hill about how she researched a largely forgotten dark moment of American history that personally affected her family and how she used research for her historical-fiction novel.

Catherina Hill

A former mayor and political speech writer, Catherina Hill found her way to historical fiction writing when she unearthed a family secret. In 1932 her pregnant grandmother had been imprisoned for three years for the crimes of fornification and manifest danger. Catherina’s new awareness of this largely forgotten mass female incarceration inspired her novel for which she is currently seeking representation and publication. You find out more about her journey at her website.

Plot Treatment

In this chapter, Lamott laments her experience with a troublesome novel. Draft after draft gets rejected not once or twice, but FOUR TIMES until she gets it right (fifth time’s a charm). In the following pages, she leads us from one depressing draft to another until she hits on the strategy that helps her write the final draft, get her advance from the publisher, and create “the most successful” of her novels (at the time Bird by Bird was published).

Unfortunately, she doesn’t define what plot is. Yet we found it helpful to know, exactly, what we’re treating before we treat it (maybe that’s why they’re called Script Doctors?).

So What is Plot?

Is it the story? The structure? The events? The themes? Character Development? All of the Above? Gardner provides us with sample plots with which to structure our novels, but he, too, doesn’t outright define plot. Bickham dedicates a whole chapter to it, “Scenic Master Plot and How to Write One,” but doesn’t give us a proper definition either. The best we get is that plot is a “key pattern.”

On the podcast, we try to define plot ourselves, with varying results, so we turn to those who provide us with some solid answers. Here are some varied definitions to plot, according to a random assortment of sources: Alan Moore, Google’s Bard, and ChatGPT.

ChatGPT (aka Chatty)

In the context of a novel, plot and structure are two fundamental elements that contribute to the overall organization and development of the story. While they are closely related, they serve different purposes.

Plot: Plot refers to the sequence of events and actions that take place in a story. It encompasses the storyline, the main events, and the conflicts that occur within the narrative. The plot typically includes the introduction of the characters, the rising action or development of the story, the climax or turning point, the falling action, and the resolution. It is the series of events that drives the narrative forward and engages the readers. The plot is the framework upon which the story is built, and it often focuses on the cause-and-effect relationships between characters and events.

Structure: Structure, on the other hand, refers to the organization and arrangement of the elements within a novel. It deals with the framework that determines how the plot is presented and how the story is told. Structure involves the overall framework of the novel, including the arrangement of chapters, sections, and scenes. It determines the pacing, the order in which events are revealed, and the development of the story arcs. The structure of a novel may vary depending on the author’s style, the genre, and the specific narrative choices.

While plot focuses on the sequence of events and the development of conflicts, structure focuses on the arrangement and organization of those events within the narrative. In essence, plot drives the story, while structure provides the framework that shapes and presents the plot effectively to the reader. A well-structured novel ensures that the plot unfolds in a coherent and engaging manner, guiding the reader through the story with a sense of flow and purpose.

In other words: What happens in the book is your plot. The order you read it in is the structure.

What's a Plot Treatment?

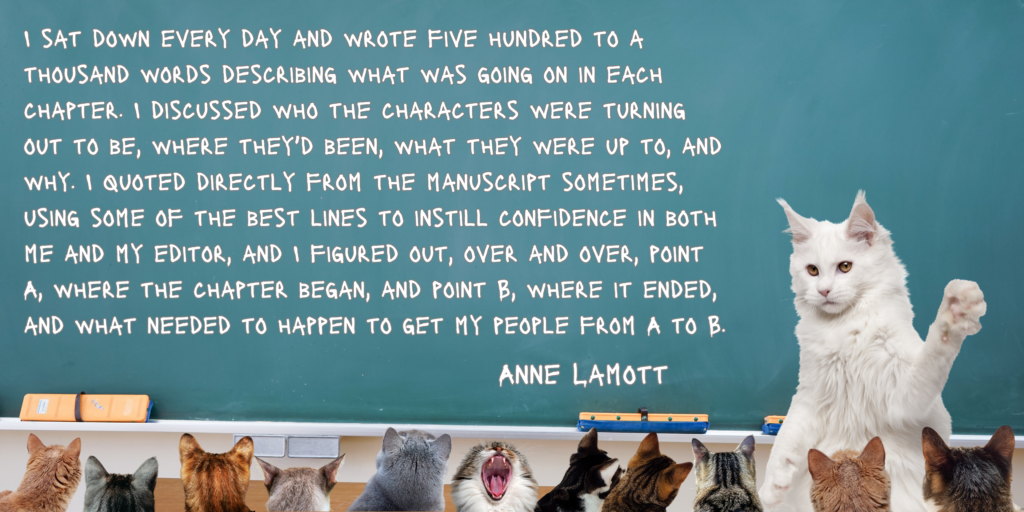

Although similar to Jack Bickham’s note card strategy, Lamott’s plot treatment is more nuanced. Instead of diagramming scene by scene (usually done before the drafting phase), each chapter in Lamott’s treatment gets a paragraph tracking the characters’ development from the beginning to the end of the chapter (after your draft has been written). Essentially, she drafts a character driven plot then edits the structure of the plot.

Below is how Anne Lamott describes her plot treatment. Yes, this will be on the test.

Don’t worry, you don’t have to memorize all the steps. The podcast’s resident teacher, Renee, has your back, Dear Reader. Here’s an easy to follow prompt to get your started. Aren’t you glad Renee shares her show notes? You’re welcome.

How to do an Anne Lamott style Plot Treatment

Write five hundred to a thousand words describing what is going on in each of your chapters. Quote your best lines to illustrate when/if appropriate. Answer the following questions:

- Who are your characters turning out to be?

- Where had they been?

- What were/are they up to?

- Why?

- Where does the chapter begin? (Point A)

- Where does the chapter end? (Point B)

- What needs to happen to get your characters from Point A to Point B.

How Do You Know When You're Done?

Continuing the (Process) Conversation

The Process of Plotting

It’s hard to find a legit author or literature professor lecturing about plot or the process of plotting. Believe me. I know. I just spent two hours sifting through vlogs and blogs trying to tell me the five simple ways to plot my novel; the only way to plot; plot this way and not that way. Did you know, you can apparently plot your novel like a freakin’ snowflake? And don’t even get me started on the plethora of videos on screen writing. The query was “author lecture on plot,” Google. Not “vapid click bait short cuts that won’t really help me plot my novel but force feed me sound bite after sound bite algorithms.” Le sigh.

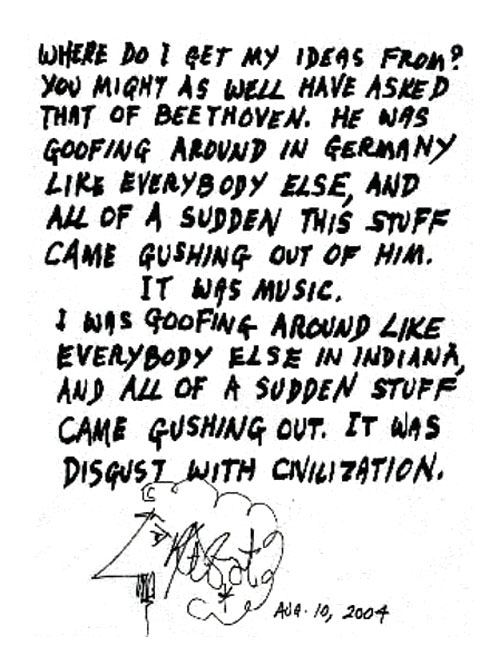

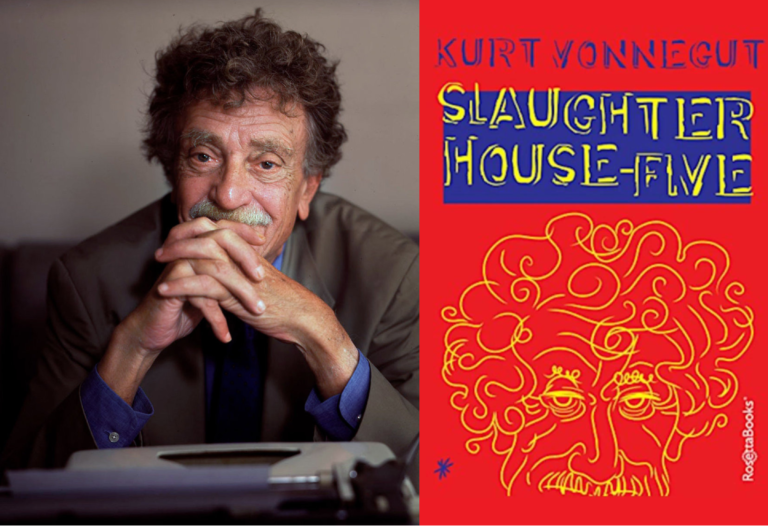

Seriously, I’ve had enough of this BS. So watch out, Dear Writer, I’m pulling out the big guns in this blog post. Let’s go back, before the world of the internet, vloggers, algorithms, AI. Let’s have a Kurt Vonnegut party! You know, the guy who wrote Cat’s Cradle, Slaughterhouse Five, and “Harrison Bergeron,” among many, many other shorts stories and novels.

Did you know, he didn’t design his plots in the shape of a snowflake? He did, however, map out the shapes of plots in his Master’s Thesis at Iowa, which was rejected, which makes him even more of a bad ass in my book. (Don’t worry, he submitted Cat’s Cradle and got his degree).

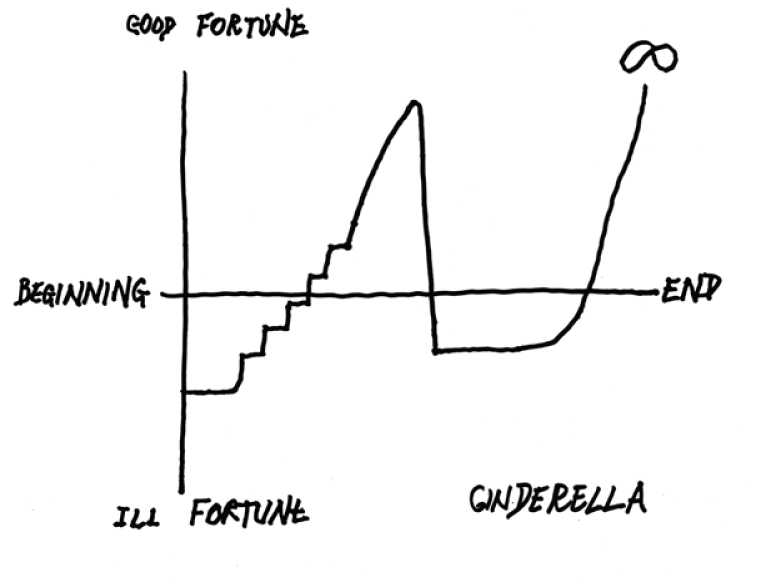

"This is an exercise in relativity. It's the shape of the curves that matter and not their origins."

Kurt Vonnegut (1922 – 2007) is a well known author of novels, short stories, non-fiction and plays. A veteran of WWII, he survived the Dresden Bombing while being held prisoner in a meat locker. With his signature satirical dark humor, he penned Slaughterhouse Five, inspired by both the name of the meat locker and his disgust with war. He has won numerous awards, such as the Guggenheim, Hugo, Audie Award, and the Science Fiction Hall of Fame.

In Vonnegut’s Master’s Thesis, Fluctuations Between Good and Ill Fortune in Simple Tales, he maps out the plot structure of the world’s most popular tales. Like Joseph Campbell, Vonnegut finds common patterns in storytelling. Vonnegut even designed graphics to illustrate these common patterns.

In this highly shared, yet aptly delivered lecture (see video below), Vonnegut teaches us both the usefulness and hubris of plot formula.

If you haven’t checked out Open Culture (or its close cousin The Marginalian), you’re missing out. You can find this video and a lot of other free resources on Vonnegut, writing in general, free lectures, cool books, and other totally free and valuable content on the web through these websites. Thanks for nothing, Google.

Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge

Authors & AI SeriesEpisode 7: Not Your Usual Words to Write By: The AI Podcasting Challenge! Is nothing sacred? After exploring how AI might steal our writing jobs, we’re...